Holiday Gifts for the Gardener

It’s that time of year again. Time to think about buying gifts for our loved ones. For gardeners there are so many things, selecting something is easy – from under $10 to over $500. Let me play Santa, offering you ideas to choose from – or things to avoid.

Let’s start with the no-no’s: Unless your sweetie has asked for more houseplants, don’t buy houseplants. The only exception to that might be an orchid in bloom – if she can consider it like cut flowers and jettison it after it finishes blooming. But in general, houseplants are work, and require space on a windowsill. Likewise avoid buying a do-it-yourself beehive kit or an earthworm farm for digesting the leftover lettuce that would otherwise go in the compost.

On the other hand, a truckload of good compost would be welcomed by almost any gardener. Just don’t have Santa deliver it on the driveway. Santa has to deliver to the garden, or near the garden. Composted barn scrapings are sold by most dairy farmers and garden centers, and by some lawn maintenance companies. Ask for “hot composted manure” or aged barn scrapings. The hot composted stuff should not have any viable weed seeds.

Garden gloves are good gifts. These range in price from $6.95 to $24.95. Now days you can even get them in pink. Me? I like the stretchy gloves impregnated with latex on the palms, but not on the backs, so hands can breathe.

Last summer I got a set of deer-repelling blinking lights. Quite innovative. They are solar powered, and emit a red LED light all night that scares deer or other pests. It is called Nite-Guard Solar (www.niteguard.com). You need at least 4 of these devices, so that one is facing each direction around the garden at eye-height of the deer or raccoon. In my limited use, they seem to be a big help. Of course, with heavy deer pressure, only an 8-foot fence is 100% effective.

Speaking of deer, another problem they present is Lyme disease, carried by ticks that deer and mice carry. There is a gaiter available that is impregnated with permethrin. These gaiters wrap around your pants to prevent ticks from getting to you – and to kill them if they try to attach to your pant legs. If you have a lots of ticks, these may be a great help. Available on line at www.Lymeez.com. This is a new version of one that I tried earlier, and the manufacturer assures me it will be ready for shipment by December 19.

I’m not, in general, a big fan of rototillers, but was given a little one to try out last spring. It’s called the Mantis tiller (www.mantis.com). It only weighs 24 pounds and digs down to a maximum of 10 inches. I used it for working compost into the top 6 inches of my vegetable garden and found that it did a good job. It starts easily and runs well.

My basic complaint with large tillers is that they can go down 18 inches or so, moving microorganisms from one soil depth to another. This little guy is less likely to do that. Big ones can also damage soil structure, particularly if wet.

This summer I got a sauerkraut crock from Gardeners Supply (www.gardeners.com) and like it a lot. Mine has a 1.3 gallon capacity, and comes with a kit that includes weights to keep the kraut submerged. It has a water-sealed air lock for the cover which allows the gases to be vented, but no extraneous air-borne yeasts or bacteria to enter it.

Every year I mention my favorite weeding tool, the Cobrahead Weeder (www.cobrahead.com). It is available everywhere now because it really works: like a single steel finger it can tease out long grass roots, prepare a place for a tomato seedling, or get under a big weed, allowing you to pull from above and below. If your Sweetie doesn’t have one, get one, and she’ll love you even more!

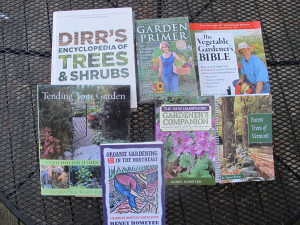

Books are always good gifts. I recently got a copy of a nice book by Vermont garden designer and author Gordon Hayward and his wife Mary called Tending Your Garden: A Year-Round Guide to Garden Maintenance. Hayward is a hands-on guy who knows a lot, and the book if full of lovely photos and sensible ideas. I also love his book, Stone in the Garden. In fact, I like all his books!

Forest Trees of Vermont by Trevor Evans is one of the nicest guides to trees I have seen. Great photos, easy-to use, it even comes with a little ruler for measuring leaves! Applicable anywhere in the Northeast. Available from Forestry Press, www.ForestryPress.com.

In general, if you like an author, any book by the same author will be good. Thus you could look for books by Michael Dirr (trees, shrubs), Barbara Damroch (general gardening), Ed Smith (vegetables) or Sydney Eddison (flowers and design). And I would be remiss if I didn’t mention my own books – they cover just about everything, but with an organic bias. My New Hampshire Gardener’s Companion is just out in an updated second edition and is relevant anywhere in New England.

Lastly, if you really don’t know what to get or are too busy to find something good, get a gift certificate to a local, family-owned garden center and let your loved pick a gift. Every serious gardener lusts after new perennials and shrubs, so why not facilitate the process with a gift certificate? And the garden centers would be happy for your business at this, a slow time of year.

Henry’s website is www.Gardening-Guy.com. Send questions to him at henry.homeyer@comcast.net.

Leaves and Compost and Mulch, Oh My!

Even if you raked your leaves in October, you probably have some more to clean up now. I do. Of course I was off gallivanting for much of October and hadn’t done any raking until recently. Still, trees like oaks and apples are still dropping leaves.

When I was a boy in Connecticut, my gardening Grampy would take the train or a bus from Spencer, Massachusetts each fall to visit us. In addition to getting some homemade apple pie and seeing his grandchildren, he came to help us rake the leaves. We lived in the country with close to an acre of lawn, I’d estimate, surrounded by a mixed hardwood forest. A lot of leaves fell –or blew- onto that lawn.

If you are of a certain age, you remember that back in the 1950’s there were no blue plastic tarps. We only had a wheelbarrow – one we called “the leaf cart” – to carry off many bushels of leaves. But Grampy was a tailor by trade, and made something to spread out on the lawn. He sewed together old sheets or bedspreads to make a large square of cloth, and brought it with him when he came each year. We raked the leaves onto that and when it was full, he drew the 4 corners together. Then, like Santa about to go down a chimney, he loaded it onto his back and carried it away.

Those leaves slowly broke down and made some of the most delicious compost you could ever imagine. Dark in color, it was loved by earthworms and was a great addition to our vegetable garden, flower pots and flower beds a few years after the leaves were collected.

It makes sense that leaves would make great compost. Trees mine the soil, bringing up minerals that end up in leaves. And, by the miracle of photosynthesis, trees make sugars and carbohydrates that build plant bodies. Re-using these elements is the original recycling. Trees have been dropping leaves and letting the bacteria, fungi and fauna of the forest break them down and re-use the elements for ages. Collecting them for use in our gardens is our way of capitalizing on a natural process.

Long ago I visited garden writer Sydney Eddison in her Connecticut garden. It was towards the end of a prolonged summer drought, one so bad that mature oaks were dying. There was a watering ban, but her flower gardens were thriving and, when I felt the soil, it was lightly damp. I asked her how she did it.

It was simple, she said. For 30 years her husband, Martin, had collected leaves each fall, running them over with a lawnmower and bagging them. He saved them in the barn, and in the spring Sydney spread out the chopped leaves and lawn grass around her perennials after they appeared. This mulch kept down weeds, attracted earthworms and enriched the soil. And it held moisture.

I use my leaves in the garden, too, though I do not bother bagging them. Most I spread over my mounded, raised vegetable beds after they have been weeded and re-shaped in the fall. They keep weeds from getting an early start, and keep out weed seeds that are blowing in the wind. Because they have been chopped, they don’t blow around much, and certainly not after a rain.

My neighbors, Susan and Joel Kinne, collect their leaves and put them in a bin they made with steel fence posts and wire mesh. It is about 4 feet on a side, and 4 feet high. I’ve seen the compost they have harvested from their bin, and it is gorgeous. Any self-respecting plant would love some in its soil. According to Joel, it takes between 2 and 3 years to go from leaf to compost, and they never bother turning the pile or doing anything else for the leaves.

I take my food scraps and the leaves and stems of kale, carrots and other veggies and toss it in a bin I made from old wood pallets. I have to admit I rarely bother to collect the compost – it is more a way of keeping vegetable matter out of the waste stream than making compost. But recently I took off one side of the bin and dug out some of the material from deep under this years’ additions.

I was amazed at the number of earthworms in the top layers – this year’s waste. There hundreds, perhaps thousands. Wriggling and squirming, small ones, medium sized ones. That’s good. They eat the food and their waste, called castings, is high in nitrogen and other minerals necessary for plant growth. More importantly, they are good sources of materials that create good tilth and texture in soil.

Deep down I harvested a bucket of black compost. It was fluffy, despite being pressed down by many pounds of matter above it. I could see bits of eggshell, but everything had been processed. I’ll mix it 50-50 with potting soil and use it to replant houseplants, giving them a fresh infusion of nutrients.

When I was a kid we jumped in the piles of leaves Grampy collected, but I think now, as a (considerably) heavier person, doing so might lead to broken bones. Still, I treasure those memories … and my leaf compost.

Henry is a UNH Lifetime Master Gardener the author of 4 gardening books. His website is www.Gardening-guy.com.

Invasive Plants

Going for a walk the other day along a public trail I was struck by the number of invasive shrubs I saw. Most trees and shrubs have shed their leaves, but burning bush (Euonymus alatus), Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii) and honeysuckle (Lonicera spp.) still have leaves on their branches. Holding leaves and producing food by photosynthesis gives them extra energy to take over the world (or their world, anyway). This is a good time to pull a few of these out because many are very visible right now.

Why bother, you might ask? Because these invasive plants which come from the China or Japan have no natural enemies here. Left alone, they can take over the landscape, outcompeting our native wildflowers and understory shrubs, although that may take decades. In some places they have created monocultures by elbowing out other plants. Most birds, mammals and insects have evolved while depending on native species for their food and shelter. Do these shrubs provide food? Yes, but it is often not of the same quality as that of our native species.

Cutting down invasive shrubs will not necessarily kill them. Some invasive trees and shrubs react by sending up multiple new shoots from their roots. Instead of one buckthorn, for example, you suddenly have several in a circle around the tree you cut down. That increases the problem instead of solving it.

I have found that buckthorns can be killed without producing the root suckers if I double girdle the tree. By this I mean I cut a ring around the tree with a pruning saw, and then cut another ring a foot higher or lower than the first cut. I cut through the bark and the green cambium layer, but do not cut into the heartwood. If I do this now, the tree will leaf out next spring and the following spring, but slowly die by the third year. Patience is the key. The technique allows you to slowly starve the roots – they can’t get any nutrition from the leaves. Many buckthorns have multiple stems, and you must girdle every one to kill the roots.

For small to medium sized invasive trees and shrubs, pulling them up is another option. I recently met with Gerry Hawkes, an inventor and forester in Woodstock, Vermont to try out a tool he developed to pull invasives (and do other tasks such as hauling firewood and moving large stones). It is a sturdy, 2-wheeled device that uses leverage to pull up a tree, roots and all. We pulled an inch-and-a-half buckthorn tree and a full size multi-stemmed honeysuckle with a trunk that was over three inches in diameter at the base.

The tool we used is called a Wheeled Post and Shrub Puller (http://

We looped a light chain around the base of the tree and then attached it to one of four notches on the puller to allow us to begin with the best mechanical advantage, which is 12:1. I pulled down on the handle using my weight and it lifted the buckthorn partially out of the ground. Then, to get an even higher lift, we reset the chain to a different notch on the front of the tool and I got the root system right out of the ground! Since this tool is on 16 inch wheels, I was able to roll the tree away with little effort.

I have also used a hand tool called a Weed Wrench that pulls small trees and shrubs. Unfortunately, the company that makes these tools has gone out of business. It was made in four sizes with a gripping mouth-part that clamps down on a trunk, and a handle that uses leverage to pry out shrubs. Two other companies are now marketing similar tools, The Uprooter (www.theuprooter.com) and the Pullerbear (www.pullerbear.com). From what I have read, neither would compete with the tool I tried last week for pulling larger shrubs and small trees.

I think that using mechanical advantage to pull invasives makes much more sense than using chemical herbicides. But I don’t have personal experience following up over several years with invasives pulled: will the scraps of roots left in the ground survive and re-sprout? It’s possible that they will. Still, I think that Conservation Commissions and Garden Clubs would be well served by investing in pulling devices to share with interested townspeople and using along public pathways.

There are no plant police. No one can tell you that your invasive shrubs must be pulled up. Nurseries may not sell them, propagate them or transport them. But I am working hard at removing mine. And even if you live in a city, it makes sense to remove invasive plants on your property. Their seeds may wash down storm drains, and end up in a wetland or river – and spread their genetic material.

Getting rid of invasive plants takes time. I recently chatted with a woman who removed all the burning bush on her property 12 years ago. She is still pulling seedlings that germinate from seeds deposited over a decade ago. But, on the positive side, pulling “thugs” gives you more room to plant other nice landscape plants. So go look for invasive plants now, and try to get rid of a few.

Henry Homeyer is a gardening consultant and coach. He speaks to garden clubs and civic organizations about many aspects of gardening. Contact him at henry.homeyer@comcast.net or visit his website, www.Gardening-Guy.com.

Picking for Vases

This is a hard time for those of us who love to go to the garden to pick flowers to grace the table. We’ve had a few weeks of cold weather, and even the hardiest of flowers seem to have faded away. So what can a gardener do?

Think outside the box. We can pick stems of shrubs with colorful or interesting bark. We can snip off branches of evergreen trees. And there are decorative grasses and even some dry weeds that have interesting form.

Actually, I do have one thing still blooming: my witchhazel (Hamamelis virginiana) shrubs are in their glory now that their leaves have dropped. They are remarkable yellow blossoms that consist of curly yellow straps. Their fall foliage is yellow and the blossoms appear while the leaves are still on the branches – and are easily missed. Now the leaves are gone and the blossoms are prominent.

Witchhazel comes in several species. There is a spring blooming variety, H. vernalis, that blooms as early as March. Some varieties of this species also have spectacular fall leaf color. The variety ‘Autumn Embers’, a spring bloomer, has great fall color. I have yet to try this species, but it’s on my wish list.

Most grasses and branches lend themselves to making big arrangements. I decided to try working with some to make something shorter as tall arrangements on the dining room table block my vision of a diner across from me. I cut stems of fountain grass (Miscanthus sinensis) which is well over 6 feet tall in my garden, but I just used the top 18 to 24 inches of each stem. They are in blossom right now, meaning that they display fluffy plumes above the foliage.

I also cut the bare red stems of red-twigged dogwood, which is also known as red osier dogwood (Cornus sericea). This is a plant that I cut to the ground each spring. New growth has bright red bark that seems to get brighter in the winter. In the wild it lives in wet places, and I grow it in moist soils, but it will grow in ordinary garden soil. I cut it back to keep the size in check, but mostly to get bright red color. Other varieties of the species produce yellow stems.

So I had bright red in the vase, and tawny beige grasses. I needed some greenery. I have lots of Canadian hemlock, but have found that the needles do not hold on well. White pine would work, but I wanted a different look. I cut a few stems of a hellebore, a perennial flower with evergreen leaves. The stems rise up a foot or so, then send out horizontal clusters of shiny green leaves, which seemed perfect. The leaves did well for a couple of days, then got droopy.

Other plants that often have good looking leaves at this time of year include European wild ginger (Asarum europaeum), dead nettle (Lamium spp.), myrtle or periwinkle (Vinca minor) and pachysandra (Pachysandra spp.). And although a vase full of just leaves may not be interesting in summer, a little greenery in a low bowl with a few stones is not bad now.

Of the leaves mentioned above, pachysandra is the best: it will last all winter in a vase, rooting and looking perky. Pick some now for use all winter.

In my vegetable garden I still have a number of plants that might also look good in a vase. Kale comes in a variety of colors and leaf types. All do well in a vase, and purple kale can be very striking. Mint also holds up for several days in a vase – and you can nibble on the leaves.

If you grew last winter’s amaryllis outdoors in a pot all summer, (hoping it might re-bloom for you this year), now is the time to give some tough love. You need to stop watering it, and let the leaves yellow and die. Cut off the leaves and keep it in a cool dark place for six weeks. It needs that dormant time if it is to re-bloom.

I usually take my amaryllis out of its pot, shake off any soil, and put it in a brown paper bag. Then I store it in my basement, which is between 45 and 55 degrees at this time of year, which is perfect. After 6 weeks I re-pot it and bring it up into the warmth of the house, but keep it out of direct sunshine for a while. Date the bag so you will know when to bring it into the light.

If you want to be sure of having a blooming amaryllis for the holiday season, go buy one now. They generally come with all you need: pot, potting soil, instructions. Don’t overwater it as the bulbs can rot. And this advice: bigger, more expensive bulbs are worth the money. The cheap ones you can get in a Big Box store will bloom, but you will probably just get one bloom stem, not two, and the blossoms will generally not be nearly as dramatic, nor be as numerous. I’ve learned the hard way.

Winter is breathing down our necks. I’m using the woodstove almost every day. And although I get a few things from my garden to put in a vase, I like to visit my local florist and buy some real flowers, too. If you’re on a limited budget, ask your florist for flowers that will last well in a vase. We gardeners all need flowers- even winter!

Henry is a garden consultant, coach, and a UNH Master Gardener. His web site is www.Gardening-guy.com.