Getting Rid of Invasives

There are still a few nice days left before cold rain, snow and cold take over our weather systems, and I try to take advantage of these last warm, sunny days. Unfortunately, I’m not the only one. No, I hope you do, too. It’s those pesky, unwanted invasive shrubs in the understory of our woods and forests that I am referring to. I took a walk recently and noticed that there are plenty of bush honeysuckles enjoying the sunshine. Many still have green leaves (some are turning yellow now), allowing them to make energy by photosynthesis and store it for winter.

Go for a walk along a country road or into your woods. If you see bushy shrubs that still have green leaves,

you are probably seeing Amur honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii). This bush honeysuckle is able to grow in sun or shade, wet or dry. It is one of the first plants to get leaves in the spring, one of the last to lose them in fall. It shades out our native wildflowers and other native shrubs. It is taking over the landscape – but you can help control it now, when you don’t have so many other gardening tasks to occupy your time.

Amur honeysuckle can get to be12-15 feet tall and wide. It is a floppy plant with yellowish-white blossoms in June and quarter-inch diameter red berries. Birds eat the seeds and then distribute them in their droppings. It takes 3-5 years from germination to the time a honeysuckle produces flowers and berries.

The roots of this bush honeysuckle tend to be quite close to the surface of the soil, so pulling or digging them out is not very difficult. I recently spent part of a morning working to eliminate honeysuckle on my property. Here is what I found.

Pulling small to medium sized honeysuckles does not require superhuman strength. I easily pulled shrubs that were 3 to 5 feet tall and wide. Larger specimens I just cut to the ground. Yes, they may re-sprout, come spring, but they won’t bloom and produce seeds next year. If I can go back each year and cut off new shoots, I will prevent the plant from spreading.

I recently spoke to Kari Asmus of Hanover, NH who has been digging up invasive plants on her property since she and her husband bought it 11 years ago. She recommends using a “weed wrench” for pulling medium to large sized honeysuckles, along with two small tree species, the glossy buckthorn (Rhamnus frangula) and common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) which are also invasive species on their property. A weed wrench (www.weedwrench.com) is a hand tool that gives you a nice mechanical advantage: it grabs onto a stem down low, and has a long handle to help you to pry out the root system with minimal effort.

Kari’s property is about 10 acres, and by keeping after the invasive plants each year, she has reduced their incidence to a point where they are not a problem. Native plants like bloodroot and wild ginger – absent when they bought the property – have returned and spread through their woods. Kari said fall and spring are the times to work on digging out problem plants. They have leaves when native plants do not. She said she has gotten to recognize the distinctive color of the leaves, even from a distance, so she can go right to a honeysuckle or buckthorn to pull it out. Seeds deposited years ago continue to germinate, but the young plants are easy to pull by hand.

The buckthorns get bigger than honeysuckles and are more difficult to eliminate. Although a honeysuckle,

if cut down, may send up new shoots at the stump, it does not send up root suckers the way a buckthorn will. Root suckers are new shoots coming up from the roots that develop into full-size trees; they can pop up 10 feet or more from the parent tree. They are a stress response by certain trees: if cut down (or sometimes if they are infected with a lethal fungus), shoots develop.

Nelia Sargent of Claremont, NH taught me some years ago how to kill buckthorns without stimulating root suckers. She double girdles a buckthorn by cutting all the way around the trunk with a hand saw. She just cuts through the green cambium layer of bark, but does not cut into the heartwood. Then she goes up 12 inches and does it again. She said it takes 3 years to kill the tree but no suckers are sent up. I tried it on a neighbor’s tree, and, by golly, it worked. However, the common buckthorn often has a trunk that can make it difficult to double girdle the tree: there are often up to a dozen trunks growing very closely together.

In my neighborhood the buckthorns have already lost their leaves, but the trees are loaded with dark berries, just waiting for hungry birds to come this winter for food. Each berry has 3-4 hard seeds, just waiting by be dropped somewhere so it can start a new tree.

So if you are looking for a good project on the next sunny day, go look for invasives and see if you can get rid of a few.

Henry Homeyer can be reached by e-mail at henry.homeyer@comcast.net or by mail at P.O. Box 364, Cornish Flat, NH 03746. His Web site is www.Gardening-Guy.com

Forcing Bulbs – Now is the Time to Prepare for Early Spring Blooms

Winter came early to Cornish Flat this year with a heavy snow in late October. I love the snow and cold, but don’t need six months of it – which could happen this year if we have snow from October till April. I am, after all, a gardening guy. I love flowers and fresh vegetables from the garden. One of the things I do to keep my spirits up is to plan for those late winter blues, the time when winter seems endless. I plant bulbs in pots each November, forcing them to bloom indoors before Mother Nature would tell them to bloom outside. I recommend it.

Forcing bulbs is easier, by far, than planting spring bulbs outdoors (there is no digging required), and you are almost certain to succeed – they are safe from predation by deer, and can easily be protected from any rodents that might be looking for a winter snack. I store my pots with bulbs for forcing in a cold cellar, one that has, on occasion, harbored mice and even red squirrels. In fact, I have learned the hard way that indoor rodents can – and will – dig up and eat bulbs – indoors or out. So now I keep my pots covered with hardware cloth (a fine-mesh metal screening available at hardware stores). But wear gloves if you cut hardware cloth to size – the edges are as sharp as razor wire.

Your first job, if you wish to force bulbs to bloom indoors next spring, is to select those that are early bloomers. Each bulb contains the information needed to decide when to bloom. You can affect that timing, but choose packets of bulbs that say “early bloomer” rather than late. I need blossoms in March, not May.

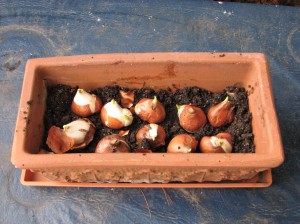

Next, select containers that will accommodate ten or more bulbs. I have some nice Italian terra cotta containers that are about 14 inches long, 7 inches wide and 6 inches deep. For daffodils or tulips, they are right for about a dozen bulbs because I plant the bulbs pretty much shoulder-to-shoulder. I don’t leave much space between bulbs the way I would if planting outside. My favorite container for forcing, however, is my cedar window box that is 3 feet long and 9 inches wide. I fill it with 30 or more daffodils each fall, and come spring it is glorious.

For the planting medium, I use a 50-50 mix of commercial potting soil and my own compost. Garden soil generally is not a good choice – it can hold too much water , which can lead to bulb rot. I put a couple of inches of planting mix in the bottom of my container, and then arrange the bulbs. I cover the bulbs with more mix, pat the surface with a hand, and if the soil mix is dry, I water lightly.

You can double your production of blooms by planting two layers of bulbs in a container. Plant big bulbs deep in the pots, add soil, and then plant a layer of crocus or other small bulbs above them. To avoid planting the little guys right over the big boys, you can mark the location of the deeper bulbs with straw from a broom. That way they won’t get pushed over as the daffodils come up.

Planted now, bulbs will extend their roots and get them well established, and then they should go dormant. To achieve dormancy, you need a cold, dark location for the container. But not too cold. You can’t leave them outside or the bulbs will be ruined. Bulbs planted in the ground never get extremely cold – they are insulated against the cold by soil and snow (unlike those put on your deck, for example). One winter, as an experiment, I shoveled the snow off a section of my vegetable garden and dug into the soil. Using a temperature probe I learned that in a winter with plenty of snow, the soil was about 35 degrees just three inches down.

I recently received several e-mail inquiries about where to store containers of bulbs for forcing. If you don’t have a cold basement, do you have an unheated mudroom or a cold attic? An attached, unheated garage might do – basically any space that gets below freezing, but not much below is good. If you have a bulkhead that is closed off to the basement it probably stays cold enough. If temperatures get much colder than 20 degrees you risk damage to some bulbs.

The time a bulb needs to be dormant varies. Tulips need at least 12 weeks, though early daffodils and most small early bulbs – crocus, snowdrops, scilla – only need 8 weeks. Years when I plant bulbs for forcing early in the fall I often leave them for sixteen weeks. If you bring your bulbs up into the warmth of the house too early they will send up greenery, but may not bloom.

To get your bulbs to bloom, bring them into the warmth of the house and water lightly. Once their little green noses appear, put the containers in a sunny window and they will perform. I rotate the containers every few days, as the stems may lean toward the sun.

Winter can be oppressive for gardeners. Getting bulbs ready for indoor blooming in mud-season is cheaper than flying to the tropics – though I’ve been known to do that, too!

Henry Homeyer can be reached at P.O. Box 364, Cornish Flat, NH 03746 or henry.homeyer@comcast.net. His Web site is www.Gardening-Guy.com

Pollarding Trees

On a recent trip to southern France I was fascinated by what some people might term “tree abuse”. The French love to turn certain trees into sculpted forms by removing all new growth each year – or most, depending on the age of the tree. The English term for this type of pruning is “pollarding”. I have decided I shall give it a try.

The English plane tree (Platanus x. acerifolia) is the most commonly pollarded tree in southern France, though I have seen other fast-growing trees treated the same way, notably lindens (Tilia spp). Plane trees are reminiscent of our sycamores (Platanus occidentalis), with bark that looks a bit like the patterns and colors of camouflage clothing. They are commonly used to line city streets and rural lanes.

The plane tree is fast growing and survives in most places – even along the Canal du Midi, the seventeenth-century canal that connects the Mediterranean to the Atlantic. I spent a day biking the canal and was amazed to see plane tree roots cross the towpath and reach into the water – like pythons slithering out of the earth and into the canal. But I noticed that the plane tree sheds branches freely, dropping small branches onto my path. I gather it is a somewhat weak-wooded tree, though perhaps not as weak as our willows (Salix spp.) or box elder (Acer negundo).

Driving through the town of Puisserguier, in the Languedoc, I admired the ‘allees’ or rows of plane trees that lined their streets. Then one day I came back and saw that all new growth had been cut off, creating an eerie, Edward Gorey-like atmosphere. Workers with a boom truck were just finishing up a major task, clearing out the clutter by cutting off all the upper branches.

These big trees showed huge knobs, scars where this had been done many times. I spoke to a tree specialist, who explained that plane tree branches can grow 6-9 feet per year, so they cut off all new growth on mature trees every other year. By cutting back the smaller branches to the trunk or a major branch, much weak wood is eliminated and weight taken off the major branches. It keeps trees from getting too tall. And it creates wonderful sculpture.

Another benefit of pollarding a tree is that it creates dense shade. Cutting back the trees encourages them to send out multiple shoots. From the scarred knobs created in previous years, a half dozen branches will erupt. That creates dense foliage. The Mediterranean sun is hot in summer, and town squares are generally shaded from its intensity by pollarded plane trees, much as our American elms once shaded Main Street.

When I return from France I will experiment with my seven-sons flower tree (Heptacodium micinioides). This is a fast-growing tree that blooms in the fall; the blossoms are small, white and lightly fragrant. It is originally from China, and has only started to become popular in the nursery trade in the last 20 years. I got mine about 10 years ago at EC Brown Nursery in Thetford, Vermont (www.ecbrownsnursery.com).

It is a medium-sized tree – the largest specimen I’ve seen is about 30 feet tall. But it can send up shoots 6 feet in a year, and I have struggled to keep mine the size and shape I want. It is near the house and several times it has attempted to send shoots indoors through a second-floor window. So I have pruned it hard, but never removed enough branches to create a pollarded look. The main trunk is now about 4-inches or more in diameter and 10 feet tall. It has one major bifurcation – where the trunk branches into 2 major branches. So I will cut off all the branches back to those two branches. Later, I may let a single new stem continue to grow and thicken, creating a higher point for pollarding.

So what else have I learned in France? I think I pamper some of my plants too much. I know that thyme, rosemary and lavender thrive in lean soil that is low in fertility. But it is hard for me to deny them some compost at planting time. Off-road biking here I have found them growing wild – thriving – in sandy dry soil, which should be a lesson to me.

Similarly, grapes here do fabulously in dry, rocky soil. One vintner, an organic grower at Domaine Bordes (A.O.C. Saint Chinian) told me that he uses no fertilizer. He said that his grapes do just fine, producing great flavor – but in smaller quantities than conventional growers who use chemical fertilizers. Grape growers often mulch with gravel in France, a technique I haven’t yet tried.

Lastly, I saw sheep’s wool used as mulch around trees. There is not much market for raw wool in France – or in the States. If you have a friend with sheep or llamas, you might be able to get some wool. It will keep down weeds, hold in moisture, and slowly break down, providing some nitrogen. Still, I’m not sure I like the look – perhaps it would be good in my blackberry patch, or around apple trees that are not in view every day.

So if you travel, observe. And send me your observations – we can all learn new techniques from each other, and from different cultures.

Contact Henry at henry.homeyer@comcast.net or P.O. Box 364, Cornish Flat, NH 03746.

Sakonett Garden and Wildmeadow

Now that I’ve put my garden to bed, I have time to think back about gardens I visited during the summer – and decide what I should try next summer. This year I had the great good fortune to spend 3 hours at Sakonnet Garden and Wildmeadow, the gardens of John Gwynne and Mike Folcarelli in Little Compton, Rhode Island. For the past 30 years they have been making and re-making gardens on about an acre of what started as a cornfield surrounding an early 1900’s Cape. They prove the point that a garden is never done: there is always something new to try.

I asked John what his garden passions have been. He said he loves playing with light in the garden: creating spaces – garden rooms – that are either bright and colorful or dark and shady. He creates special effects with plants – enclosing silver-foliaged plants with dark green hedges, for example. He enjoys showcasing dramatic plants, placing them in full sun at the end of a long dark path. He is also passionate about restoring meadows so that birds like bobolinks and meadowlarks can breed and succeed.

Like me, John is a plant collector, and one who tests plants to find which ones grow and look the best. At one point he and Mike had 500 rhododendrons, for example. They have thinned that collection down to “just” 100 or so.

As I walked through the gardens I made notes of things I might like to try, both plants and planting techniques. One of the first things I noted was their capricious use of unusual items as hose guards. Hose guards allow you to drag a 100-foot hose through the garden and go around corners without knocking over or damaging plants. They used baseball bats half buried in the soil and antique croquet wickets. I really liked their use of tool handles – old shovel handles that had snapped off – as hose guards. It is recycling at its best.

The gardens are divided up into rooms with walls, generally at least 6 feet tall. Some were made of living material –hedges or vines on trellises – and others were made from a variety of non-living materials, including stone.

One wall that caught my attention was made of logs. Logs – suitable as firewood – were simply stacked up, each piece about 2 feet long. The wall was a good 8-feet tall and made of logs that varied in diameter from an inch to six inches or more. There is a door that leads out of the room – with a gate. An iron frame that supports logs over the door; the door itself was made of flat welded iron with metal screening attached.

Training vines can be tricky, especially if you want them to travel laterally through the air. The solution they found was to roll out 25 feet or more of chicken wire, then shape it into a long roll. A three-foot width of chicken wire, when rolled up tightly, makes a form that is structurally strong enough to be suspended between trees or walls and support vines. They intermingled 2 plants: winter creeper ( Euonymus fortunei) and Japanese holly (Ilex crenata), training them to flow through the air.

John and Mike grow a number of plants that are generally considered invasive pests – things like giant hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum) and a variegated-leafed form of Japanese knotweed (Polygonum cuspidatum). And although I do not recommend using such plants, they have figured out ways to do so – and to contain them responsibly.

Giant hogweed grows to be 6-10 feet high and has flowers that can exceed 2-feet in diameter. They are careful to pick the flowers before they go to seed, thus preventing them from spreading. Me? I grew it before I knew better, and was able to eradicate it when I learned it can be invasive. It will grow in sun or shade, wet or dry, and has roots that go down 3 feet or more into the soil. I still watch for it, and occasionally an old seed will germinate and create another plant.

Japanese knotweed (seen along roadsides and streams and commonly called ‘bamboo’) spreads by root, so they contain it in sections of concrete well pipe – the kind that is used to contain shallow hand-dug wells. Each piece of the pipe is 30 inches in diameter and 3-4 feet long. The pipe makes a terrific planter – it is simple, sturdy, and creates a root zone deep enough for most plants, but also deep enough to contain wandering invasives.

Their garden also uses snow fence as walls for rooms. Most snow fence is 4-feet tall, but they special order 6-foot snow fence made by Griffin Fence Company in Griffin, Georgia and have it shipped to them. They support the fencing with 4-inch square posts and grow vines or hedges to make the fencing disappear, especially since they paint it black. It works well for them as deer proofing.

If you’d like to see these phenomenal gardens, John and Mike will be holding a series of open days next summer, and possibly a day of workshops next spring. Their Web site, www.sakonnetgarden.com will list the dates of their upcoming events – though the Web address may change by spring.

I will never have the time and energy to build gardens as fine as those of Mike and John, but next summer I hope try to try some of their ideas.

Henry’s Web site is www.Gardening-Guy.com.