Holiday Gifts for the Gardener

Gardeners are easy to shop for. We all need the practical (rubber-palmed stretchy garden gloves, watering wands, garden scissors, plant labels) and appreciate the whimsical (a nice garden gnome to surprise the grandkids). Gardening books keep us occupied during the long winter nights, and garden tools keep us dreaming of perfect peonies. Here are some suggestions for the gardener you love.

This year I discovered Tubtrugs. They are multipurpose, brightly colored, somewhat flexible containers made of food grade plastic that I like to fill up with weeds. I also use them when harvesting veggies or carrying hand tools; you can fill one with water to soak a dry potted plant or wash a small dog. They are easy to carry – handholds are built in. They come in 4 sizes from about 4 gallons to about 20 gallons. I have the 2 smaller sizes, which cost $11-14. Available at your local garden center or from www.tubtrugs.com.

As much as I don’t like plastic, I found another plastic product that is very handy: an Oxo brand watering can. As with other Oxo products, I find it not only functional, but handsome – and these come in a variety of colors. I like that the spout lets you see the water level inside when filling it up, and it rotates for storage (snuggling up, sort of, against the reservoir). The rose, which breaks the stream of water into a spray, is very fine for watering delicate plants, but I often just pull that off and water directly from the slender spout. They come in 2 sizes: 2 gallon ($28) and an indoor model that is just 3 quarts ($18). Available locally or on line.

Each year I have to tout my favorite weeding tool, the CobraHead Weeder, as it works so darn well, and I have met so many gardeners that just love it. It is a single piece of steel with a small, eye-shapede head and a curved handle. It has a nice bright blue, recycled plastic handle. It gets under weeds to pull from below while I tug on the topside; I use it when planting, too, stirring up the soil and teasing out grass roots. I like that it serves lefties as well as righties, and is light enough to please elderly weeders as well as big lunks like me. Cost? About $25. Available locally or at www.cobrahead.com or 1-866-962-6272.

Books help get gardeners through the winter. We read and plan when we can’t weed and plant. I recently got a very handsome, glossy-photo book by Jeremy and Emily Gettle, co-owners of Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds. He is quite a character – he started at age 3 and was growing 2 acres of vegetables by age 18. He started his own seed company when he was just 22 years old and now 33, he has quite a large operation – and a book.

The book, The Heirloom Life Gardener: the Baker Creek Way of Growing Your Own Food Easily and Naturally, is interesting and full of personal stories and anecdotes by Jeremy. He is opinionated, which I like, too. Best of all, it has a directory of garden vegetables that not only tells you how he grows them, but guides you to save your own seeds. It’s $30 in hardcover.

Another book I like is Ancestral Plants: A Primitive Skills Guide to Important Edible, Medicinal and Useful Plants of the Northeast by Arthur Haines. This is a fascinating technical book for survivalists, among others. It tells you not only about edible and medicinal plants, but which ones to use for making your own rope or are useful when starting a fire without matches. Haines is young (forty-one), and a serious scholar, having just written a 1,000 page taxonomy of plants.

Haine’s book gives information available in no other book I have found. So, for example, he tells you to eat eastern prickly gooseberries one at a time so that the crushing of the berry is done with teeth, not the palate (to avoid the prickles), and that it is high in Vitamin C, antioxidants and pectin so it can easily be made into jam. Each plant has at least 2 excellent color photos and 2 pages of text. $23 in paper available locally, or from www.anaskimin.org.

Each year I find some nice products from Gardeners Supply Company in Burlington, VT (www.gardeners.com or 888-833-1412). This year I like their pesto storage cubes for freezing pesto or tomato paste. They have attached lids, and fit into trays for storage. At $7.95 for 8 cubes they are a good gift. I also like their Root Storage Bin which costs $34.95. It is a sturdy wire bin lined with jute fabric designed to hold carrots, beets etc. in a cool dark cellar. It allows you to layer moist sand in it, keeping the veggies from drying out. It fits in a fridge I use for storing veggies. They also sell the Tubtrugs mentioned above. Since Gardeners Supply is an employee-owned company that supports lots of good causes, I enjoy supporting them, too.

I’ve been using LED lights this fall to pamper my houseplants, and I find my plants are much healthier this year. Best of all, for 42 watts of electricity I am getting the equivalent of 250 watts of light, and the spectrum of light, the company says, is just right for making plants happy. I got mine from Sunshine Systems (www.sunshine-systems.com or 866-576-5868). Each unit costs about $150 and is suitable for illuminating 5 square feet of plant space. The lights are designed to let you connect several together, which is handy.

Lastly, as an author I would be remiss if I didn’t mention my own new book: Organic Gardening (Not Just) in the Northeast: A Hands-On, Month-by-Month Guide (Bunker Hill Publishing). It’s a collection of my best writings from the past 10 years, organized around the calendar year. It’s $17.50 from your local bookstore or from my website (www.Gardening-guy.com).

So give Santa a hand. Go get something nice for the gardener in your family. And remember to try buying local first: local bookstores, local garden centers – only buy on the Web as a last resort! And Happy Holidays to you all.

Henry Homeyer is the author of 4 gardening books. His Web site is www.Gardening-guy.com.

Forcing Bulbs – Now is the Time to Prepare for Early Spring Blooms

Winter came early to Cornish Flat this year with a heavy snow in late October. I love the snow and cold, but don’t need six months of it – which could happen this year if we have snow from October till April. I am, after all, a gardening guy. I love flowers and fresh vegetables from the garden. One of the things I do to keep my spirits up is to plan for those late winter blues, the time when winter seems endless. I plant bulbs in pots each November, forcing them to bloom indoors before Mother Nature would tell them to bloom outside. I recommend it.

Forcing bulbs is easier, by far, than planting spring bulbs outdoors (there is no digging required), and you are almost certain to succeed – they are safe from predation by deer, and can easily be protected from any rodents that might be looking for a winter snack. I store my pots with bulbs for forcing in a cold cellar, one that has, on occasion, harbored mice and even red squirrels. In fact, I have learned the hard way that indoor rodents can – and will – dig up and eat bulbs – indoors or out. So now I keep my pots covered with hardware cloth (a fine-mesh metal screening available at hardware stores). But wear gloves if you cut hardware cloth to size – the edges are as sharp as razor wire.

Your first job, if you wish to force bulbs to bloom indoors next spring, is to select those that are early bloomers. Each bulb contains the information needed to decide when to bloom. You can affect that timing, but choose packets of bulbs that say “early bloomer” rather than late. I need blossoms in March, not May.

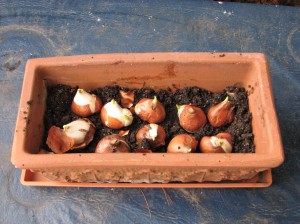

Next, select containers that will accommodate ten or more bulbs. I have some nice Italian terra cotta containers that are about 14 inches long, 7 inches wide and 6 inches deep. For daffodils or tulips, they are right for about a dozen bulbs because I plant the bulbs pretty much shoulder-to-shoulder. I don’t leave much space between bulbs the way I would if planting outside. My favorite container for forcing, however, is my cedar window box that is 3 feet long and 9 inches wide. I fill it with 30 or more daffodils each fall, and come spring it is glorious.

For the planting medium, I use a 50-50 mix of commercial potting soil and my own compost. Garden soil generally is not a good choice – it can hold too much water , which can lead to bulb rot. I put a couple of inches of planting mix in the bottom of my container, and then arrange the bulbs. I cover the bulbs with more mix, pat the surface with a hand, and if the soil mix is dry, I water lightly.

You can double your production of blooms by planting two layers of bulbs in a container. Plant big bulbs deep in the pots, add soil, and then plant a layer of crocus or other small bulbs above them. To avoid planting the little guys right over the big boys, you can mark the location of the deeper bulbs with straw from a broom. That way they won’t get pushed over as the daffodils come up.

Planted now, bulbs will extend their roots and get them well established, and then they should go dormant. To achieve dormancy, you need a cold, dark location for the container. But not too cold. You can’t leave them outside or the bulbs will be ruined. Bulbs planted in the ground never get extremely cold – they are insulated against the cold by soil and snow (unlike those put on your deck, for example). One winter, as an experiment, I shoveled the snow off a section of my vegetable garden and dug into the soil. Using a temperature probe I learned that in a winter with plenty of snow, the soil was about 35 degrees just three inches down.

I recently received several e-mail inquiries about where to store containers of bulbs for forcing. If you don’t have a cold basement, do you have an unheated mudroom or a cold attic? An attached, unheated garage might do – basically any space that gets below freezing, but not much below is good. If you have a bulkhead that is closed off to the basement it probably stays cold enough. If temperatures get much colder than 20 degrees you risk damage to some bulbs.

The time a bulb needs to be dormant varies. Tulips need at least 12 weeks, though early daffodils and most small early bulbs – crocus, snowdrops, scilla – only need 8 weeks. Years when I plant bulbs for forcing early in the fall I often leave them for sixteen weeks. If you bring your bulbs up into the warmth of the house too early they will send up greenery, but may not bloom.

To get your bulbs to bloom, bring them into the warmth of the house and water lightly. Once their little green noses appear, put the containers in a sunny window and they will perform. I rotate the containers every few days, as the stems may lean toward the sun.

Winter can be oppressive for gardeners. Getting bulbs ready for indoor blooming in mud-season is cheaper than flying to the tropics – though I’ve been known to do that, too!

Henry Homeyer can be reached at P.O. Box 364, Cornish Flat, NH 03746 or henry.homeyer@comcast.net. His Web site is www.Gardening-Guy.com

Pollarding Trees

On a recent trip to southern France I was fascinated by what some people might term “tree abuse”. The French love to turn certain trees into sculpted forms by removing all new growth each year – or most, depending on the age of the tree. The English term for this type of pruning is “pollarding”. I have decided I shall give it a try.

The English plane tree (Platanus x. acerifolia) is the most commonly pollarded tree in southern France, though I have seen other fast-growing trees treated the same way, notably lindens (Tilia spp). Plane trees are reminiscent of our sycamores (Platanus occidentalis), with bark that looks a bit like the patterns and colors of camouflage clothing. They are commonly used to line city streets and rural lanes.

The plane tree is fast growing and survives in most places – even along the Canal du Midi, the seventeenth-century canal that connects the Mediterranean to the Atlantic. I spent a day biking the canal and was amazed to see plane tree roots cross the towpath and reach into the water – like pythons slithering out of the earth and into the canal. But I noticed that the plane tree sheds branches freely, dropping small branches onto my path. I gather it is a somewhat weak-wooded tree, though perhaps not as weak as our willows (Salix spp.) or box elder (Acer negundo).

Driving through the town of Puisserguier, in the Languedoc, I admired the ‘allees’ or rows of plane trees that lined their streets. Then one day I came back and saw that all new growth had been cut off, creating an eerie, Edward Gorey-like atmosphere. Workers with a boom truck were just finishing up a major task, clearing out the clutter by cutting off all the upper branches.

These big trees showed huge knobs, scars where this had been done many times. I spoke to a tree specialist, who explained that plane tree branches can grow 6-9 feet per year, so they cut off all new growth on mature trees every other year. By cutting back the smaller branches to the trunk or a major branch, much weak wood is eliminated and weight taken off the major branches. It keeps trees from getting too tall. And it creates wonderful sculpture.

Another benefit of pollarding a tree is that it creates dense shade. Cutting back the trees encourages them to send out multiple shoots. From the scarred knobs created in previous years, a half dozen branches will erupt. That creates dense foliage. The Mediterranean sun is hot in summer, and town squares are generally shaded from its intensity by pollarded plane trees, much as our American elms once shaded Main Street.

When I return from France I will experiment with my seven-sons flower tree (Heptacodium micinioides). This is a fast-growing tree that blooms in the fall; the blossoms are small, white and lightly fragrant. It is originally from China, and has only started to become popular in the nursery trade in the last 20 years. I got mine about 10 years ago at EC Brown Nursery in Thetford, Vermont (www.ecbrownsnursery.com).

It is a medium-sized tree – the largest specimen I’ve seen is about 30 feet tall. But it can send up shoots 6 feet in a year, and I have struggled to keep mine the size and shape I want. It is near the house and several times it has attempted to send shoots indoors through a second-floor window. So I have pruned it hard, but never removed enough branches to create a pollarded look. The main trunk is now about 4-inches or more in diameter and 10 feet tall. It has one major bifurcation – where the trunk branches into 2 major branches. So I will cut off all the branches back to those two branches. Later, I may let a single new stem continue to grow and thicken, creating a higher point for pollarding.

So what else have I learned in France? I think I pamper some of my plants too much. I know that thyme, rosemary and lavender thrive in lean soil that is low in fertility. But it is hard for me to deny them some compost at planting time. Off-road biking here I have found them growing wild – thriving – in sandy dry soil, which should be a lesson to me.

Similarly, grapes here do fabulously in dry, rocky soil. One vintner, an organic grower at Domaine Bordes (A.O.C. Saint Chinian) told me that he uses no fertilizer. He said that his grapes do just fine, producing great flavor – but in smaller quantities than conventional growers who use chemical fertilizers. Grape growers often mulch with gravel in France, a technique I haven’t yet tried.

Lastly, I saw sheep’s wool used as mulch around trees. There is not much market for raw wool in France – or in the States. If you have a friend with sheep or llamas, you might be able to get some wool. It will keep down weeds, hold in moisture, and slowly break down, providing some nitrogen. Still, I’m not sure I like the look – perhaps it would be good in my blackberry patch, or around apple trees that are not in view every day.

So if you travel, observe. And send me your observations – we can all learn new techniques from each other, and from different cultures.

Contact Henry at henry.homeyer@comcast.net or P.O. Box 364, Cornish Flat, NH 03746.

Spring has sprung

Spring really is here in Cornish Flat, NH. I know that we stand a chance of frost, so I am not planting frost sensitive plants. But I have onion plants in the ground, as well as some small lettuce plants and spinach I planted indoors back in March.

wall-o-water

I planted one tomato plant on May 7 and then enclosed and protected it with something called a “Wall -o-Water”. This is a water filled teepee made of plastic baffles. It heats up during the day, and holds in warmth at night. It supposed to protect plants from frost even if it gets down to 24 degrees!

primroses-on-may-6-2011

My primroses are blooming like crazy, especially one called Primula kisoana. It is a nice magenta, and spreads by root.

If you are looking for more spring activities, I suggest you read my new book, “Organic Gardening (not Just) in the Northeast: A Hands-On Month by Month Guide. It is organized by the month, so you can see what I do in April and May, for example.

More on Starting by seeds

The seeds I’ve started indoors this year are coming along. I planted onion and leeks on March 1, and they are growing well. I planted shallots, a variety called Prisma, but had low germination rate and re-planted. Once again I got just 10-25% germination. Not sure what the problem is, but I will buy shallot sets and plant them in May outdoors. Sets are those little “bulbs” available at garden centers.

I planted 3 artichokes on March 15, and all 3 are up and looking good. Two leaves each. I planted peppers then, and they are still just getting going. I keep them on a heating pad, 2 seeds per cell. I will cut off one seedling in a week or two once I see which plants are doing the best. The heat mat is great for any heat-loving plant such as peppers, tomatoes or eggplants.

I also planted 18 beets indoors, something I’ve never done before. I’ll transplant them outdoors as good-size seedlings in May. I planted a variety called Moneta (from Johnnys seeds), which doesn’t require thinning if spaced appropriately. Beet “seeds” are not seeds at all, but seed capsules containing 1-4 seeds. So beets generally need to be thinned almost right away, which is tedious work.

I will plant Moneta an inch and a half apart, and then eat every other one once they start to get big enough to enjoy as greens. That will leave the plants 3 inches apart to reach maturity, which is good spacing.

My new book is out and selling like hotcakes! Here is a quote from Paul Tukey, formerly the publisher of People, Places and Plants Magazine, and the author of The Organic Lawn Care Manual,” He says, “Henry Homeyer’s writing and advice have become an indispensable fabric of the Northeast landscape, as comfortable as your crusted leather boots and gloves, and as reliable as your grandfather’s spade with the old ash handle. This book won’t stay on the shelf; it will reside in the potting shed or on the garden bench. The advice, like the gloves, will be well worn, but it will never wear out.”