Plan to Grow Winter Vegetables

Posted on Sunday, January 2, 2022 · Leave a Comment

I am probably not the only person who is determined to lose a little weight after all those delicious but fattening meals and desserts served up over the holidays. One way to feel satisfied and lose weight is to eat more salads and enjoy more vegetables. That’s my plan, anyway, and I recently took stock of what is lingering on in my storage fridge. I still have some nice veggies from summer that still taste good and are satisfying my hunger.

Try growing Kohlrabi this summer.They’re tasty and keep well

Digging around the vegetable drawer I noticed several kohlrabi I grew last summer, but had not been touched in months. I was prepared not to like them because they had been stored so long. I peeled one, chopped it into half-inch cubes, and added to my nightly salad. It was delicious! It’s even tasty as low calorie snack food just by itself.

Kohlrabi is in the cabbage family, but not well known or much grown, It looks like a space alien in the garden: it is an above-ground root vegetable of sorts. Round or oblong, it can be green or purple, with leaves poking out of the beet-like “tuber” on bare stems. It is crunchy, and tastes a bit like broccoli, which is in the same family. It can be used to make coleslaw when grated with carrots.

Buy a packet of kohlrabi seeds and plant them in early June or late May. They are fast-growing plants and only need a bit of space to grow well. If you want kohlrabi all winter for adding to stir fries, plant a green one called ‘Kossak’ which gets large – up to 8- or 10-inches in diameter – and stores for up to 4 months in a cool, high humidity place like the vegetable drawer our your fridge. I get seeds from Johnny’s Selected Seeds in Maine, but it is also available from High Mowing, Gurney’s and Park Seeds, among others.

I also found half a purple cabbage that had been lurking in my vegetable drawer since September. I expected it to be stale, but it was fine. Cabbage is easy enough to grow, but I often don’t bother because I don’t use it much – it is cheap and readily available. I grated some and added it to a green salad, adding color and bulk.

Onions are sold as plants which grow better than onion sets, or little bulbs

I had a great onion crop last summer. I buy onion plants from Johnny’s Seeds most years instead of babying seed-started plants indoors. When I start from seed, I start them under lights around March 1. When I start my own, even with intense light close to the seedlings, they are always a bit flimsy. Some of the plants I get from Johnny’s are nearly as thick around as a pencil, and take off and start growing immediately. The kind I grow are yellow onions, one called ‘Patterson’. They keep for months in a cool location, but will sprout and soften if left in the warm kitchen in a bowl.

The plants come in bundles of 50 to 60, according to their catalog, but last year I got closer to 100 plants per bundle. Onions don’t like competition, so weed early and often. Space your onions about 3 inches apart in the row, with rows at least 8 inches apart. They like fluffy, rich soil so be sure to add lots of compost and stir it in well. You can also start onions from “sets”, which are like little bulbs – but less vigorous than plants.

What else am I eating from the garden now? Garlic. It is easy to grow, but if you didn’t plant any last October, you’re probably out of luck. It sets its roots in the fall, goes dormant, and pops up early in the spring. It is rarely available to purchase in the spring. I was out in California one spring and bought some soft-necked garlic in the spring, and it did fairly well here. You could try planting some of last year’s garlic, come spring, if you have any left over but it’s not recommended.

Potatoes are also a mainstay of my winter menu. I know, they are not usually recommended for dieters. But that is partly because of how they are served. They are a healthy starch, but many of us tend to load up potatoes with sour cream or butter. Add them to a stew or stir fry, and they are still tasty but much less calorific.

I went 20 years once without buying a potato. I grew plenty, and saved out some for planting each spring. By only eating my own, I went a few months without any while waiting for my new crop to be ready. But it was a matter of principle to only eat my own. Commercial potatoes, if not raised organically or following IPM guidelines, can carry heavy pesticide loads.

The trick to getting lots of potatoes is to grow them in full sun. You can get potatoes where there is only 6 hours of sun per day, but the more sun, the more potatoes. And don’t let the potato beetles defoliate your plants. Check leaves, including the underneath side, for orange egg masses or larvae often when they are starting to grow. They can multiply exponentially if you let early beetles multiply.

Gardens aren’t just for food. They can be for fun too.

Having a vegetable garden is, of course, a certain amount of work. But it provides me not only with good, healthy, organic veggies, it saves me lots of money and keeps me active in the garden. As we get older, the more exercise we get, the better. So start reading the catalogs or websites of seed companies, and plan what you will plant, come spring. Me? I can’t wait!

Henry lives and

gardens in Cornish Flat, NH. He is the author of 4

gardening books. You can reach him by email at

henry.homeyer@comcast.net.

World of Wonders

Posted on Thursday, December 30, 2021 · Leave a Comment

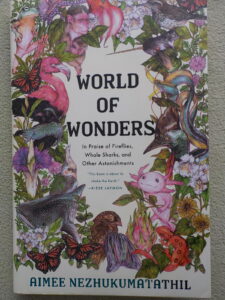

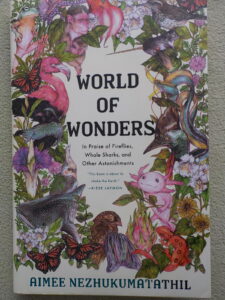

World of Wonders is a delight to read

One recent morning I decided it was time to finish reading a small book of essays I had started long before, and savored, but had (inexplicably) put off finishing. “World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks and Other Astonishments” is a delight, from start to finish. Its author has a name that could wrap around my own more than once, and is almost unpronounceable at a first try: Aimee Nezhukumatathil.

I think of the author as Aimee, and I know she would not mind. She is young, full of life, with a “joie de vivre” that lights up every room she enters, I should think. But what encouraged me to share her book with you was the last essay, ‘Firefly (Redux): Photinus pyralis’.

In her essay about fireflies she recounts her experience teaching a poetry class at an elementary school in a suburban town where fireflies are common. When she mentioned fireflies, most of her students thought she was making them up. Of twenty-two students in her class, seventeen had never seen a firefly. Instead of spending early summer evenings outdoors catching fireflies and putting them in jars to bring indoors, they were texting friends or playing videos games.

That same morning I read a review in the New York Times of a biography of E.O. Wilson, a hero of mine and a biologist who is now 92 – but still active and observant. He began his scientific life studying small creatures ignored by most of us: ants. At age of 13 he found a species of red fire ant from Argentina that had never been reported in the United States. He went on to study at Harvard and write more than 30 books and 500 scientific articles.

So what do these two wonderful people have to do with you or me? They have great curiosity about the natural world. And we do, too. We are gardeners and as such spend time pondering why any given plant bloomed magnificently last year, but meagerly this year. We offer our palette of plants more water, or less. We add fertilizer, or we don’t. Would an early June “haircut” delay blossoming, and encourage a less lanky plant? Good gardeners pay attention to the details of life.

I believe that we all have a responsibility to share our passion with our children and our grandchildren. Or the boy across the street who stops, while walking his dog, and asks us questions about our garden. Most scientists and citizen scientists had someone in their early life who encouraged them to ask questions and showed them something special that amazed them.

When I was in the third or fourth grade my family took a week’s vacation together in Maine. We stayed at Goose Cove Lodge on Deer Isle, a delightful rustic place run by a retired biology professor, Dr. Ralph Waldron. Dr. Waldron offered guided walks along tidal pools and in meadows of wild flowers off the beaten track. My parents, my sister Ruth Anne, and I always went on these walks. Dr. Waldron not only let me see new things, he encouraged me to take samples and bring them back to the lodge to study.

And so I began my career as a citizen scientist. He taught me how to preserve flowers and leaves by pressing them in a simple press to make herbarium mounts. He taught me not only the common names of plants, he taught me their Latin names. He encouraged me to see similarities and differences in plants. He let me preserve small sea creature in glass jars with formaldehyde as a preservative so that I could take them home, along with my flowers. I began to appreciate the vast diversity of the natural world, and its beauty.

We returned to Goose Cove Lodge every summer for a few years, and I deepened my interest for the natural world each time we went. In college I majored in biology, in part because of Dr. Waldron’s influence.

Sometimes it seems that the news about the natural world is always depressing: global warming, I read this morning, is causing rising temperatures in ponds, causing more poisonous blue green algae to flourish. Elsewhere today I read that a living species somewhere becomes extinct every day. And so on. What can you and I do about it?

We can garden. And we can introduce the life outdoors to a young person. An Eight-year old, perhaps. If we take joy in what we do, and share pour excitement with a young person, they too may become an E.O Wilson, or an Aimee Nezhukumatathil.

We don’t need to be scientists to encourage young people to love and respect our natural world. My gardening grandfather, John Lenat (1888 to 1967) probably never finished high school. He came to the United States as a young man from Germany. He loved to garden, invited me to spend time with him each summer, and I absorbed a lot from his way of doing things. He let me putter in the garden and do things to help, but only as much as I wanted. He never asked me to weed, and let me take worms from his compost pile to catch fish.

As a New Year’s resolution this year, I hope you will think about connecting a young person with the outdoors. With our gardens, or the bugs and toads that live there. Maybe together we can all make a difference. Just maybe, if we each make an effort to live sustainably, we can save the world.

Henry is a UNH Master

Gardener and the author of 4

gardening books. He lives in Cornish Flat, NH. Reach him by e-mail at

henry.homeyer@comcast.net.

Winter Mulching and Composting

Posted on Monday, December 20, 2021 · Leave a Comment

Although we had a little snow on the ground for much of November and December, snow has been scarce as we move towards the New Year. If this continues, does this have any consequences for our gardens? Yes, it can.

If we have bare ground and a very cold winter, roots will see colder temperatures than they might prefer. Like that pink fluffy fiberglass in the walls of our homes, snow is a great insulator. Snow holds tiny pockets of air, holding in warmth from the soil and preventing icy north winds from stealing warmth from the soil.

Lacking snow, what can one do? Fall leaves are great. If you have a leaf pile somewhere, think about moving some to spread around your most tender plants, especially things planted this year. Perennials and woody plants are most vulnerable to the cold their first winter.

This tree peony is well protected from the cold with leaves and burlap

I have a tree peony that I planted this year, quite a pricey plant. Unlike the common perennial peony, the stems of the plant are woody and do not die back to the ground each winter. And the blossoms are much more dramatic: up to a foot across.

I have done two things for it: I mulched around the base with chopped leaves, and I wrapped some burlap around it to protect the stem itself and the flower buds that are already in place for next summer. This will help to keep January’s cold winds from affecting it. We have done the same for tender heirloom roses, with good success. Shrub jackets made of synthetic, breathable material are also available instead of making your own from burlap.

I worry about voles chewing through the burlap, nesting inside, and then eating the tender bark of my young tree peony. I had some ‘Bobex’ brand deer repellent and decided to spray the burlap. It is made with rotten eggs and other nasty stuff and might deter voles.

This tree peony had 10-inch wide blossoms

My wife, Cindy, and I recently used burlap to prevent hungry deer from eating the leaves and branches of a pair of large yews. First I drove four one-inch diameter hardwood stakes into the ground around each six-foot tall shrub. I stood on a step ladder and used a 3-pound short-handled sledge hammer to drive the stakes in about a foot. Then we draped the burlap over the top of the stakes and stapled the burlap to hold it in place on windy days. We used a heavy duty carpenter’s stapler as a desk stapler would not work. We have done this before, and the deer cannot get to one of their favorite winter meals. The wrapping we did was open to the top as deer can’t reach that high, but smaller plants should be completely wrapped.

A simple A-frame protected this boxwood from the snowplow on our road last winter

Another hazard for plants is heavy snow and ice that fall off rooves, or is pushed up by snow plows. Last winter I made three A-frame plywood protectors for small shrubs to protect them. Each used four stakes and two pieces of plywood. At the top of each stake I drilled a hole and slid through both a piece of wire that connected the two stakes. This is a cheapskate’s way of avoiding the cost of hinges. And it works just fine! If the ground is not frozen, push the stakes into the soil, but if it is frozen, it should stand up fine anyway.

Later, after the holidays, recycle your evergreen tree in the garden. After I take off decorations, I use my pruners to cut off all the branches. This helps me find every last little ornament, and then I have a nice stack of evergreen branches to use around or over tender plants. The branches are good windbreaks for small shrubs, and hold snow through winter thaws as they sit over tender perennials. If you use a fake tree, watch for discarded trees waiting curbside, and snag one (or more) for use in the garden.

A simple A-frame protected this boxwood from the snowplow on our road last winter

Composting in winter is a chore that some gardeners don’t bother doing. But you should, as it is a waste to put your moldy broccoli in the landfill. For many gardeners the compost pile is a considerable distance from the house, requiring warm coats, gloves – and perhaps snowshoes. But there is an easy solution.

Invest in an extra garbage can, a large one that will hold 30 gallons or more. Place it inconspicuously but conveniently near the house. Ideally, you have a kitchen door behind the house, and can bring food scraps to it without bundling up for the cold.

Your winter compost will freeze, and will not break down during the cold months. So chop any big things to smaller pieces to allow it to pack down well. Then, come spring, you will have to shovel the material into a wheelbarrow and bring it down to your regular compost pile after it has thawed.

Of course, commercial compost bins are available to buy instead of the Mr. Thrifty 30-gallon plastic can. But since compost does not break down outside in winter, a plastic bin may not hold all the material you produce. If you fill the first one garbage can, an extra can is a smaller investment than a bin made just for compost. And those rotating bins? I’ve rarely met anyone who keeps turning them every week anyhow.

So get creative and protect your plants however you can. And if you have a great idea, write me so I can share it with others. My best to you all for the holidays!

Looking for a present to give? Henry is selling his book “Organic

Gardening (not just) in the Northeast: A Hands-On, Month-by-Month Guide”.

This is a collection of his best

articles. Send a check for $19 to Henry Homeyer at PO Box 364, Cornish Flat, NH 03746 or for faster service, use PayPal at

www.Gardening-Guy.com.

Winter Plantings: Paperwhites and Amaryllis

Posted on Tuesday, December 14, 2021 · Leave a Comment

As winter drags along, I long for warm sun and green plants surrounding me outdoors. It’s much too early to start spring seeds (even indoors), but I can plant some flower bulbs. I love paperwhites and amaryllis, and both are readily available for planting now – and they will bloom indoors while it snows outside.

Paperwhites are a type of daffodil specifically for forcing indoors now. Most grocery stores sell them, as do garden centers and feed-and-grain stores. They usually cost about a buck a bulb, and will produce flowers in four to six weeks. They are not hardy in New England, so don’t bother saving the bulbs to plant outdoors. Just enjoy them, and accept that they are a one-shot deal.

5 paperwhite bulbs fit into this soupbowl with gravel

I should warn you that paperwhites have strong scents, and not everyone is enthralled with their smell. But I like the scent, which I can smell once I walk into a room with freshly blooming paperwhites. If you don’t like strong-smelling musky scents, there is one variety that is barely fragrant: ‘Grand Soleil d’Or’. Instead of the traditional white blossoms, these bulbs produce gold or yellow blossoms.

If you are in a hurry for blossoms, and can select your bulbs from a bin, select those that already have started to grow. They are just aching to grow. Select a nice bowl or pot that will hold water, and get some small stones – three quarters of an inch to an inch is a good size. Garden centers sell white marble chips for this, but you can pick up stones from your driveway or garden, too. Just rinse off any stones before using them.

Arrange the 3 to 5 bulbs on a layer of stones, then fill in around the bulbs with more stones. The stems and flowers will get up to 18 inches tall, so they may tip over if not firmly seated and surrounded with stones.

Next, add water until it just kisses the bottom of the bulbs. You do not want the bulbs to sit in water. Those dry roots will quickly wake up and extend into the pool of water around the stones. Top up the water as needed, but try not to let it go dry.

Some people wait until the bulbs have grown an inch or two, drain off the water, and replace it with a 7 to 1 dilution of gin or vodka. This will, I am told, produce shorter, sturdier stems that will not flop. Or use rubbing alcohol and dilute a bit more, 11 to 1.

An amaryllis bulb does not need much soil and needs to be planted like this

A more expensive – but more dramatic – flower for forcing is amaryllis. This is a tropical flower originally from South Africa – and many are still imported from there each year. Properly cared for, your investment in an amaryllis bulb will produce a plant that will last for up to 75 years, blooming every year!

Amaryllis bulbs are big: they are anywhere from 2 to 4 inches across. They are often sold with a kit that includes an appropriate-sized plastic pot, the bulb, and enough potting soil to plant it in.

Smaller amaryllis bulbs are younger and less expensive, but you get what you pay for: a $5 amaryllis at a Big Box Store will probably produce one stem with three or four large blossoms. A $12 bulb will be bigger and should produce two stems with eight or more blossoms. In time, your small bulb will get bigger if you care for it properly.

Planting an amaryllis is easy. You should plant it in a good potting soil, not soil from the garden which may stay too wet and get compacted. It is important that the bulb NOT be buried in soil. It may rot if you do that. The shoulders of the bulb should stick up above the soil line, up to one third of the bulb. The potting soil should be lightly moist, not dry or soggy when you plant it.

Place your amaryllis is a sunny window and wait. Sometimes when you buy an amaryllis it will have already started to grow in the box. I like that, as it means that my amaryllis will start growing for me right away.

Other times an amaryllis will sulk for weeks, doing nothing. There is nothing I know of to encourage it to grow, though maybe whispering encouragement to it will help. Only do that, however, when you are the only person in the room!

Amaryllis stems tend to lean toward the light, so rotating the pot every few days will help to keep it growing straight up (and give you something to do). You may need to insert one or more thin bamboo sticks and tie with yarn to help keep the heavy blossoms – up to 4 inches across – from pulling the stem over.

After the first stem has bloomed you may get a second stem. You can cut off the first stem after it is finished blooming. Sometimes the first and second stems grow at the same time, which leads to a little pushing and shoving in the pot, much like teenagers. Once a stem is finished blooming, you can cut it off.

After blooming, keep it in the pot, and put it outside in a sunny location all summer, but bring it inside by October 1. Remove from the pot and let it dry out. Cut off the leaves and place it in a paper bag and keep in a cool, dark place for 5 or 6 weeks. Then pot it up, and it will bloom again.

So if you miss gardening, get an amaryllis or some paperwhites. And spring will be along in no time!

Looking for a present to give? Henry is selling his book “Organic Gardening (not just) in the Northeast: A Hands-On, Month-by-Month Guide”. This is a collection of his best articles. Send a check for $19 to Henry Homeyer at PO Box 364, Cornish Flat, NH 03746 or order use PayPal at

www.Gardening-Guy.com.

Creating a Winter Wreath

Posted on Thursday, December 9, 2021 · Leave a Comment

Winter is upon us and it may seem there is little for a gardener to do. No weeding, nothing to plant, no flowers to pick. But last year’s garden may still have some remnants that, with a little imagination, can create something pleasing to the eye. I went out to my garden in early winter to see what dry flowers still were standing after my garden clean up, and saw plenty to work with. I picked plenty and set them aside for making winter wreaths and arrangements.

Wreath form made with grape vines

I like wreaths, and in the past I have made them to decorate an outdoor space such as a blank wall or door. Instead of using a wire wreath form, as many people do with evergreen wreaths, I used grapevines to make the basic form for my wreath. You can, too.

Go to a wooded area and look for vines climbing a tree. Grape vines are common in hardwood forests, but often strangle trees, so removing some grapevine is actually a good thing to do. Cut a 15-foot length of grapevine that is about as thick around as your ring finger. It is important to use living, not dead, vines; they are a greenish white inside and flexible. Dead vines are brittle, brown, and not suitable.

Begin by forming a vine circle 14 to 16 inches in diameter by overlapping (or twisting) one half of the vine over the other half – the same way you would start to tie your shoelaces. Then grasp one of the loose ends and weave it around the vine circle in loops, over and under, pulling it tight as you go. Then take the other end of the vine and weave it around the circle.

The great thing about this grapevine wreath is that you can just slide stems of dry flowers in between the vines and natural tension will hold them in place. In fact, I had to use a screwdriver to lift the vines at times in order to slide the stems in place. But I also use thin florists wire to tie together more delicate things like grasses and add them to the wreath.

Winter wreath with a dusting of snow

Here are some of the plants I used in my winter wreath. Sedum ‘Autumn Joy’ is a deep brown and stands up well in the winter garden. Fountain grass (Miscanthus sinensis) ‘Morning Light’ provides a light grown, fluffy material, as the seed heads are still present. Mine got knocked over by ice earlier in the winter, and then after the ice melted, it stood back up again!

What else? Various hydrangeas have flower panicles that are dry and delicate but still attached at this time of year. I used some flowers from one called ‘Quick Fire’. I like it for wreaths because the panicles are not huge, the way many of the PeeGee hydrangeas are, or Annabelle. If your panicles are too big, you can prune parts off to make them more suitable for a wreath.

I wanted some greenery in the wreath and could have pruned off some twigs from either white pine on hemlock, but had some Christmas fern right near the house and used that instead. I’m not sure how long it will hold up in a wreath, but looks good now. Hemlocks tend to drop needles fairly quickly, but anything used as a Christmas tree would be fine – Balsam fir or blue spruce, or example. Or snip some stems off your Christmas tree when you take it down.

Close-up of winter wreath

For color I went to my brook and gathered some winterberry (Ilex verticillata) growing alongside it. This shrub has bright red berries in winter, and although it prefers a moist location, but it will grow in ordinary garden soil, too. In summer it is pretty ordinary looking, but is fabulous when covered with red berries in winter. You need both male and female plants to get berries. One male is fine for five females.

The last addition to my winter wreath were some stems of teasel, a biennial weed hated by mid-western corn farmers. It gets in their machinery and gums up the works – and it grows 6 feet tall. The flowers and seed heads are two-inch cylinders that are very prickly. The stems have thorns, but these can be rubbed off while wearing gloves, making them easier to work with.

Because teasel is a biennial, it is easy to control: I pull most of the first-year plants when they are small. I leave just a few to grow and produce flowers. Six plants or so are nice. They stand up all winter and contrast well with the snow.

If you are not interested in making a wreath, or don’t have the time, pick some stems of anything interesting still standing in the garden, and put them in a dry vase. I leave some flowers with seed heads for the goldfinches and juncos to munch. Things like black-eyed Susans and purple coneflower are nice for them. I always leave some snakeroot, too (Actea racemosa., formerly Cimicifuga racemosa), as it is a tall plant that stands above the snow.

Dry plants cut for use in wreath

Lastly, if you are looking for dried flowers to decorate with, don’t forget the weeds. Walk through an un-mowed field and you will see plenty of dry flowers standing proud in the snow. Or take a walk along a country road and look for shrubby things with interesting branches or seed pods. With a little imagination, they can be used to create beauty.

Henry is the author of 4 gardening books and a long-time UNH Master Gardener. He lives in Cornish Flat, NH. Reach him by e-mail at

henry.homeyer@comcaset.net.

In Praise of Kale, the Misunderstood Vegetable Hero

Posted on Tuesday, December 7, 2021 · Leave a Comment

Like Rodney Dangerfield, kale doesn’t get enough respect. I’ve been told that it only became a commonly grown vegetable in the 1970’s when salad bars ordered it to use as the bed upon which other edibles like tomatoes, carrots and cukes slept on in nearly ordered arrangements. No one actually ate kale. But that has changed, at least with the Birkenstock crowd. Like me, for one.

Kale became the carpet for other veggies because it is a deep, rich green, and seemingly never wilts. It is the toupee of veggies, always looking neat and presentable. I often pick a few leaves and place the stems in a jar of water on the kitchen counter to remind me to include it in soups, stews, scrambled eggs and more. And to admire.

December kale with Rowan, our new dog

On a recent raw December morn I took our new dog out for a walk. Rowan is a year-old Irish setter/golden retriever mix we adopted just before Thanksgiving. As he zoomed around the property I stopped to see how our kale is doing. Still healthy, despite occasional temps down to 15 degrees, and now covered with wet snow. I picked a few leaves and brought them up to include in a soup or salad.

Kale is crunchy. In a salad I cut it finely, blending it in with lettuce, although my wife, Cindy, recently made a kale salad. She also used walnuts, crispy rice and dried cranberries – and it was delicious. She massaged the fine-cut leaves with olive oil for a couple of minutes first to help make it less crunchy.

It is one of the more nutritious greens. Compared to iceberg lettuce, it has two and a half times more fiber. It has more thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, pantothenic acid, Vitamin B6 and folate than iceberg lettuce. It is a great source of Vitamin A, Vitamin C, Vitamin K, calcium, and potassium. It has twice the calories of iceberg lettuce, but neither is a high-calorie food. You can eat all the kale you want and not gain an ounce of fat.

Kale in the garden in February

One of my favorite ways to eat kale is in a green smoothie for breakfast. I use about 2 cups of kale removed from the center rib, a banana, half an avocado (if I have one), half a cup of orange juice and a cup and a half of water. Oh, and I squeeze half a lime into the mix, and grate in some fresh ginger if I have it. I chop the kale very, very finely because my older blender doesn’t liquefy it, even though the dial says “Liquefy”. I don’t want to have to chew my smoothie.

Sometimes I add frozen blueberries or raspberries to the mix, or if I want a cold smoothie, I substitute ice cubes for some of the water. In summer when I have lots of greens I try to add 4 or more leaves of other greens – lettuce, Swiss chard, or whatever looks good. Spinach is good, and very nutritious. It freezes well after a brief blanching.

Growing kale is easy. I rarely find the leaves eaten by insects, though some readers have written me about flea beetles (or something) eating holes in the leaves. You can stymie most bugs by covering the plants with a layer of “row cover”. Row cover is a spun agricultural fabric that looks like those dryer sheets available to reduce static and add fragrance to laundry. But this stuff comes in long 60-inch wide pieces. Wires are sold to form hoops over small plants, but you can drape it right on bigger plants. It is great for keeping potato beetles away from you spuds, too.

Kale is a big plant. I grow it 18 inches apart in a wide, raised bed. It grows best in full sun, but if sun is at a premium in your garden, it will do fine in part shade. Hot afternoon sun and dry soil is not ideal for kale. I recommend adding plenty of compost in the planting hole, and some slow-release organic fertilizer.

Sometimes I start kale from seed indoors six weeks before planting it outside, but if too busy, I just buy some started plants from my favorite farm stand. If you start your own kale indoors, you may get tall, lanky plants – due to not enough light inside. No problem. Bury some of the stem. Just pinch off some lower leaves, and plant the kale deep in the soil so it is not flopping over when it goes in the ground.

A few ingredients for my soup – dry beans, kale, scallion, garlic

I make a great winter stew using kale and other garden vegetables that I have either stored or frozen. It can be either vegetarian or not. It is loosely based on a Portuguese stew I ate years ago on Cape Cod. I don’t think you need a step-by-step recipe, nor do I know the exact proportions, but I share with you my carnivore version and you can make your own according to your preferences – and what you have available.

I start by slicing a pound of Linguica Portuguese sausage into smallish cubes and browning in olive oil with onions and/or leeks (which I always have in the freezer). If you don’t find Linguica, substitute any spicy sausage like Andouille Cajun sausage.

Then I add water and tomatoes. I freeze tomatoes whole in September, so I use those, chopped up, but you could use a 28 oz can of diced tomatoes. Into the stew goes a couple of cups of chopped kale. Then I add herbs – parsley, fennel seed, oregano and marjoram. And carrots, for sweetness.

Lastly I add something to give the stew rib-sticking goodness: either potatoes, winter squash or cooked dry beans. I let the stew simmer until hunger overwhelms me, but I always make plenty as it is good warmed up for days.

So remember to plant plenty of kale next spring. It won’t disappoint you.

Henry’s book, “Organic

Gardening (not just) in the Northeast: A Hands-On, Month-by-Month Guide” is available from him, signed, for $19. Send a check to PO Box 364, Cornish Flat, NH 03746. Or, if you want to use PayPal, go to his website,

www.Gardening-Guy.com.

Brightening the Dark Days of Winter

Posted on Tuesday, November 30, 2021 · Leave a Comment

This is the darkest time of the year: not only are the days short, clouds obscure the sun much of the time. Many of us find the gloom oppressive, especially when there is neither enough snow to ski, nor ice to skate on. And for gardeners, there is little we can (or wish to) do outside. So what do I do?

First, I go to my local grocery store or florist and buy cut flowers or potted plants. For $10 or $15 I can brighten my outlook considerably. The most economical to buy are potted plants. They will, with a minimum of care and forethought, bloom for weeks – or even for months. Here are a few of my favorites:

Christmas cactus. It should be called a Thanksgiving cactus, really, because they usually bloom well before Christmas. Buy one in full bloom, or that has a mix of blossoms and buds. They need moderate light indoors, but not hot afternoon sun. Temperatures of 60 to 70 degrees are best for success. They should not be allowed to dry out completely, but neither do they want to be kept soggy. They like humidity, so place them in a saucer of small stones and add water. Never let the pot sit in water.

Cyclamen. Another low-light plant. This one suited for even less light than Christmas cactus. If you give it any direct sunshine, an hour or two of morning sun is plenty, but indirect light is better.

Cyclamen really are not fussy, and bloom for weeks

Water your cyclamen only when dry, which depends on the temperature and relative humidity. I find picking up the pot tells me a lot: if dry, it weighs very little, when moist, it is heavier. If you go too long, the flowers will flop as if to say, “Look at me, I’m dying of thirst!” But they recover quickly. Place your plant in a saucer of water and let it suck up water. But don’t let it sit in water for long.

My mother loved African violets, and did well with them. I remember doing an experiment with my new Chemistry Set for Young Scientists when I was in the fourth grade. I made a solution of tannic acid, and put a drop on a leaf. Overnight, it burned a perfect hole! Great experiment until my mother asked me if I had done something to her plant.

I have not had great luck with African violets here in New Hampshire (they may have heard about my experiment, way back when). I largely heat with a wood stove, and keep the house warm, but quite cool at night. I finally read an article that said one should never let the temperature in the room they are in drop below 70 degrees. So I no longer try, though I have recently read that temps down to 60 degrees are okay.

If you want to grow them, keep them consistently warm in a bright room but not in direct sunshine. They like high humidity (hence do not like woodstoves) but do not tolerate soggy roots. Water from the bottom, but water once a month from above (to flush out any fertilizer salts). Never let water get on the leaves. Pinch off spent blossoms or yellowed leaves.

My absolute favorite house plant is an orchid called Phalaenopsis or moth orchid. Buy them in bloom, and they will bloom for many weeks. Direct sunlight can scorch the leaves, but they need a bright room. These are tropical orchids so like warm temperatures. But cool nights are good – down to 55 degrees.

Moth orchids in their native environment grow in trees. So the soil mix they come in is generally a special orchid mix made of bark chips, and perhaps a little perlite or vermiculite. This mix allows water to run right through it. Be sure that if it comes with an inner pot and an outer pot, to pour out water after watering from the outer pot, which normally has no drainage. Or just lift the inner pot and run water through in your sink. Otherwise you will kill your orchid. Water once a week, or if exposed roots turn silvery white.

According to the experts, tree orchids such as these do best with good air circulation. Me? I find that in a room with people coming and going there is enough air movement to keep them healthy. I do grow them over a saucer of pebbles and water to increase humidity, and grow them in the bathroom where steam from the shower helps.

But if you have no patience with house plants, or believe you cannot grow them, buy flowers for a vase. Most cut flowers will last a week in a vase, many will last longer. Most stems cost between $1.50 and $3.00. Buy an odd number of stems – 3, 5, 7 or 11, depending on your budget.

The vase for displaying cut flowers should be about half as tall as the stems are long (or a little less). But that rule is not firm. If the arrangement looks good to your eye, it is fine. Use a clean glass or pottery vase for best results, but if you want to use Grandma’s silver vase, go ahead. Elegance is good.

Cut flowers generally come with a little packet of white powder. Use it. It helps to keep the water from getting full of bacteria or fungus that will clog the stem, keeping it from taking up water. Pull off any leaves that would otherwise go in the water. You can also use a teaspoon of Clorox in a quart of water. Never put cut flowers near a radiator or wood stove.

So buy something in bloom. It will help to dissipate the gloom of short, dark days. Oh, and about that African violet: I confessed, and did not get punished. But I never experimented with her houseplants again.

Henry’s book “

Organic Gardening (not just) in the Northeast” is available from him for $19. Mail a check to Henry Homeyer at PO Box 364, Cornish Flat, NH 03746, or order from his website,

www.Gardening-Guy.com.

Holiday Gifts for the Gardener

Posted on Tuesday, November 23, 2021 · Leave a Comment

This tree guard keeps voles from damaging young trees

Ready to shop! Every time I turn on the radio or open a newspaper, there are articles about supply chain issues. Even the reliable old US Postal Service is saying deliveries may well be delayed. So share some garden produce this year or shop at a local, family-owned business when you can.

Food is a great gift. You don’t need fancy fruit shipped from Oregon if you made plenty of tomato sauce or quince jelly this year. Share the harvest. A quart of dried cherry tomatoes contains a lot of love and work. You had to grow, harvest, wash and dehydrate. Only people dear to my heart will rate such a gift.

My dream gift? A friend, loved one or reader sending me a nice card, along with a homemade certificate for four hours of weeding in my garden. Or two hours. Working in the garden with a friend or relative can be a great way to strengthen a friendship. Politics don’t matter in the garden. I might suspect my brother-in-law didn’t vote the way I did in the last election. But if he will bring his chain saw and help me take down and cut up a 12-inch diameter boxelder I want removed, send me the gift certificate!

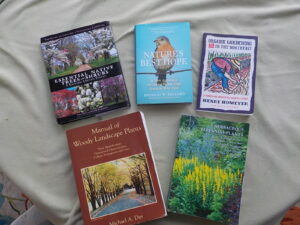

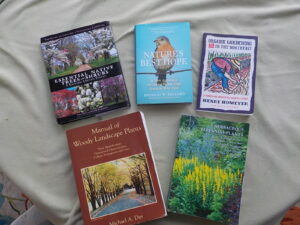

Gardening books make great presents

Books are great gifts, and books printed in the United States should be readily available at your local bookstore. My first choice for a book to give? Doug Tallamy’s book, Nature’s Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation That Starts in Your Yard. It explains how what we plant can affect the planet, especially our pollinators and birds. And all of us, really.

I’ve re-printed my last

gardening book, and will be selling it at a discount directly to you, signed. It’s a collection of my best

articles organized around the calendar year. It’s titled

Organic Gardening (not just) in the Northeast: A Hands-On, Month-by-Month Guide. Signed and mailed to you for just $19. Send a check to Henry Homeyer at PO Box 364, Cornish Flat, NH 03746. I will try to figure out how to reduce the price on my website,

www.Gardening-Guy.com where it is currently for sale at $21 if you want to use PayPal.

What else at the bookstore? Essential Native Trees and Shrubs for the Eastern United States by Tony Dove and Ginger Woolridge is a great companion for Doug Tallamy’s book. Michael Dirr has written lots of great tree books. He is informative and opinionated. Allan Armitage is just as opinionated and thorough about flowers as Dirr is about trees. Or get a gift certificate and let your gardener pick her own books at the local bookstore.

Garlic clips work well for me to deter deer

If deer are a problem in the garden of your loved one, I find nothing better than “Fend Off Deer and Rabbit Repellent Odor Clips”. Available at Gardeners Supply and other retailers. A package of 25 sells for about $20. I use one or two per shrub to keep deer away all winter. They clip on with a clothes-pin style attachment. They contain just garlic and soy oil, no chemicals.

I recently wrote about using hardware cloth (wire screening) to keep voles from chewing off bark and killing young trees. Since then I have used plastic spiral tree guards that are easy to install and will protect against sun scald in winter, too. They are inexpensive and can be re-used (I will remove them in the spring). They are sold as Rainbow Professional LTD White Spiral Tree Guards at OESCOinc.com or by calling them at 413-469-4335. They sent my order out the very day I called.

I like this Lowe anvil pruner

Also available from OESCO are some pruners that I like a lot. OESCO is a small company based in Conway MA catering to orchard professionals. The pruners are made by a German company, Lowe with 2 dots over the O, not to be confused with the American retailer Lowe’s. The pruners are of the anvil type, designed and manufactured well. They sell a size nice for small hands (Lowe 5.107) and a larger size, too. OESCO sells replacement blades and parts.

Of course every gardener needs a good weeding tool. My favorite is the CobraHead, and has been for years. They now have a mini-Cobrahead which is designed for smaller hands. Available from CobraHead.com or 866-962-6272 or at your local garden center. It has a single curved tine like a steel finger that will tease out roots from below while you tug a weed from above. I emailed the owner, Noel Valdes, who told me there are plenty in stock.

Root Slayer spade and CobraHead weeder are excellent tools

I found a wonderful shovel for digging in tough areas with lots of roots. It’s called the Root Slayer and is available from Gardeners Supply and a few other retailers. I’ve used mine all summer, and love it! Great for cutting though sod, too. It has a sharp blade and teeth along the sides for slicing roots.

Lastly, think about a gift certificate at your local nursery or garden center for plant purchases in the spring. Plants are always good.

Henry lives, writes and

gardens in Cornish Flat, NH. His e-mail is

henry.homeyer@comcast.net. He is the author of 4

gardening books.

Roasting Garden Produce

Posted on Tuesday, November 16, 2021 · Leave a Comment

One of the reasons I garden is that I love to cook and to create wonderful, flavorful dishes that I might not get elsewhere. I think many gardeners share that inclination. One of the techniques I have not used much is roasting vegetables, but I recently did some roasting, and will do some more. I find it sweetens and intensifies flavors.

It all started when I was baking some potatoes. I had the oven at 425 and decided to make some kale chips at the same time. I ran down to the garden and picked some leaves. I took four of them, sliced the leafy part off the stems, and chopped coarsely to one-to two-inch squares. Then I sprinkled them with olive oil, tossed them well and dusted them with salt. I put them on a cookie sheet and roasted until crisp – ten minutes seemed just right.

I’ve made kale chips before, but was never enamored of them. This kale had been hit by frost several times, which made the leaves sweeter. And I cooked them at a higher temperature than I’ve done before. I also made a small batch: Cindy and I ate them all before dinner. In the past I have stored kale chips in a well-sealed glass jar, but they got soggy anyway. Still got kale in the garden? Give it a try.

Baked potatoes are a classic dish, and easy to make. A few tips: grow some russets next year, they are best for baking. And brush them with as little melted butter or olive oil to help crisp up the skins. But plan ahead: it takes 45 to 65 minutes at 400 degrees to bake a potato. The bigger the spud, the longer it takes. You should be able to poke a fork or knife in easily when cooked. Oh, and don’t forget to poke some holes in the skin when you start – I’m told they can explode if you don’t.

Frozen peppers thawing before roasting

I usually freeze fresh bell peppers in the fall. I find they are great for cooking, and can be tossed in a salad, too. No blanching: I just wash and wipe dry, then seed and slice them and freeze in a zipper bag. I decided to try roasting frozen peppers now to see how they would do.

I spread out a couple of cups of frozen sliced peppers on a clean cloth towel on the counter, while pre-heating the oven to 450. They thawed quickly, and I patted them dry. I put them in a bowl and tossed them with some olive oil. Then I removed one half and put on the cookie sheet for cooking; the other half I sprinkled with dried oregano flakes and a little salt before spreading on the pan. Put down parchment paper or aluminum foil to simplify clean up.

The peppers needed 25 to 30 minutes until they were soft and slightly charred. I did not remove the skins, though people who roast them whole tend to do that. If you are roasting peppers as a side dish, be aware that roasting them reduces the size considerably – a cup of sliced peppers doesn’t make much of a dish.

A few days later I got a nice pork roast and cooked it at 350 degrees for over an hour. This gave me a medium-hot oven just begging to roast veggies. I roasted beets, carrots, onions and tomatoes, and all were delicious!

The beets were medium sized – 2-inches in diameter or so, and took an hour or a little more to feel well cooked. I wrapped them loosely in aluminum foil after cutting off the leaves. I left the tails (roots) on the beets, and an inch or so of the stem and leaves. Cut beets tend to bleed, and I didn’t want that.

The carrots I just tossed into the roasting pan after a cleaned them well and cut off the stems and tips. If you have small carrots they don’t take as long as beets, so you can put them in later in the cooking process. Onions I peeled and roasted whole. While roasting they caramelized, turning sweeter. Good used cold in sandwiches!

Roasted tomatoes with basil

I tried roasting my tomatoes by either cutting tomatoes into half-inch slices and also just cutting them in half. I found the halves were easier to serve – the sliced tomatoes tended to fall apart. Later, when roasting peppers, I also roasted three more fresh tomatoes at 450 degrees after sprinkling them with dry basil. Even at 450 it takes an hour or so to get them to collapse and brown up.

Roasting tomatoes does give them a very nice, intense tomato flavor. Years ago I roasted quite a few with the idea of storing the results in the freezer. It worked well. I roasted them longer than I did just now: I roasted them until almost all the moisture was out, probably at a lower temperature. Then I put them in zipper bags and froze them for use in winter sandwiches. I took the frozen tomato pieces and thawed them in a toaster oven.

Each year I grow some winter squash. My favorite is the Waltham butternut. It is a light-brown squash with a bulbous, seed-filled distal end, and a narrower section with no seeds that extends to the attachment point on the vine. Mostly I peel them, remove the seeds and chop into cubes to include in stews and stir fries.

Waltham butternut squash are great when roasted

Recently I roasted a butternut squash and was delighted not only by the flavor, but also by the fact that I did not have to peel the skin. When serving (after an hour at 350 degrees) I scooped the cooked meat out of the skin. But later, I tried a bite of the skin, and it was soft and delicious. Vegetable skins generally are full of vitamins and minerals, so I shall plan on eating squash skins from now on (with the exception of Blue Hubbard skins which are so thick and leathery).

So as you plan your garden for next year, think about growing veggies you can roast. They are perfect comfort food for long winter nights.

Fall Color: It’s More than Maples

Posted on Tuesday, November 9, 2021 · Leave a Comment

New England is known worldwide for its fall color. People swarm here from all over, largely to see the color of our sugar maples. As I senior citizen I am legally entitled to drive around at 25 miles per hour, holding up traffic and enjoying every brilliant red tree I see. But I rarely do – I’m too busy in the garden, most of the time. But there is a lot more to see than maple trees.

For color I really enjoy the leaves of oaks and American beech. They hold on to their leaves much longer than the maples, often long into winter. Why is that? Probably because they have only migrated north after the last ice age, and where they came from – the American South – they did not have to drop leaves in the fall. That’s one theory I have read, anyway.

On sunny fall days the yellow leaves of beeches just glow. I enjoy them in the woods or alongside the road, but do not plant beeches or recommend them to others. There is a disease caused by the Neonectria fungus that is spread by scale insects. It mars their smooth gray bark and eventually kills the trees. So I advise enjoying them where you see them in the woods. Yes, there are systemic poisons you could apply to kill the scale insects and perhaps hold off the decline of an existing tree, but I don’t want poisons in my landscape.

Oaks vary considerably in their fall color. Deep reds, purples and browns are often mixed with reds depending on the locale, soil and species. Yellows and greens are often displayed on leaves, too.

One of the great features of oaks is their stamina: The “George Washington Oak” was only recently declared dead – at the age of 600 years. It grew in Bernards, NJ and grew to have a trunk circumference of 18 feet and reach 100 feet tall. Oaks routinely live to be 300 years old if not abused by soil compaction and urban smog. Yet they are relatively fast growing when young: the pin oak can grow12 to 15 feet in 5 to 7 years.

Although I am tremendously keen on promoting native trees and shrubs, I do believe we can have a few imports, and one of my favorites for fall color is a large shrub call disanthus (Disanthus cercidifolius). It is listed as a zone 5 plant, but I have had one in my Zone 4 garden for at least 10 years. Mine is now nearly 8 feet tall and wide. In the fall the leaves turn a brilliant purplish red, as good as or better than that dreaded invasive, burning bush (Euonymus alatus), that was so popular before it was listed as an invasive. In October some years (but not every year) my disanthus bush has tiny pink-purple blossoms that you will only notice if looking for them. They come right out of the bark, without stems.

Witchhazel (Hamamelis virginiana) is one of the few native trees that flower in the fall. It is an understory tree that will grow in shade, partial shade or full sun. It has yellow fall foliage which pretty much obscures the yellow blossoms until leaf drop in October or November. Then the blossoms become prominent. The blossoms have 4 strap-like, curly petals are less than an inch across. Witchhazel usually has many, many blossoms.

Scientists have only recently discovered what pollinates witchhazel. Bees and other pollinators are no longer buzzing around when they bloom. But witchhazel produces nectar and brightly colored flowers to attract insects. No one knew what pollinated them until naturalist Bernd Heinrich discovered that is the night-flying owlet moth. Apparently that moth can raise its temperature by 50 degrees by shivering. If only that would work for me!

The Seven-Sons Flower Tree (Heptacodium miconioides) is another fall bloomer. It was imported from China in 1907, but sales never took off. It was re-introduced in 1980 and immediately became popular for its fast growth (I have seen stems grow 6 feet in a year) and fabulous shaggy bark in winter. Its mature height is said to be 25 feet, but I keep mine to 15 feet with pruning. It will grow in full sun or partial shade.

This year mine was still blooming in late October. The blossoms are small, white, lightly fragrant and appear in clusters of seven at the end of branches. Later, if there is no frost, the sepals turn pink.

There is one other tree I grow that blooms in the fall each year, usually in September, and then only a few blossoms at a time. It is a magnolia, a hybrid called ‘Jane’, one of the “Little Girl’ series. It blooms first in late spring, and then re-blooms once a month or so with a few fabulous deep pink 4-inch blossoms, with a light pink interior.

Jane grows in six-hours of sun or more in moist, rich soils. The leaves are deep green and glossy, good enough to put in a vase. It is listed as a Zone 5 plant, but does well in Zone 4 for me. Because it blooms in late spring, frosts in April do not affect it. It is a small tree, perhaps 15 tall, with a nice rounded shape.

Spring and summer will always be the best seasons for flowering trees, but I like to extend the seasons with trees that flower and look good well into winter.