Feeding the Birds – Without Buying Seeds

This year, given the plethora of squirrels in the universe, I feel that I should just buy a dump truck-load of black oil sunflower seeds and drop it on the lawn in front of the deck. Then maybe the squirrels would let my timid titmice get to the feeder. Maybe not. But there are other ways to ensure our feathered friends get lunch.

Long before farmers of the mid-West began cultivating sunflowers in mile-long fields, birds survived our winters here. How? They ate the seeds of our native flowers and shrubs, and the little bugs that lived on them. Let’s look at a few trees that birds depend on – not just now, but throughout the year.

Two of the best trees for birds are white pine and Canadian hemlock. Each is used by 25 to 40 species of birds. Some birds eat the seeds. Some use them for shelter, getting out of the winter wind or spending the night nestled safely in the branches. Others build their nests in them. Birds need places for all those things in order to survive.

Unfortunately, both pines and hemlocks grow to be taller than your home, given a couple of decades. White pine (Pinus strobus) grows an average of 2 feet per year, so you shouldn’t plant one near the house. But if you want to block the view of the neighbor’s rusty cars lurking by your property line, several white pines can be nice. They get to be 20 to 40 feet wide, so if you plant them 10 to 15 feet apart, they will fill in the gap nicely.

Canadian hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) will grow in full sun or deep shade, but does not do well in wet, soggy soils. It grows fast, especially in sunny locations. I’ve read that it takes 20 years before the trees start to produce cones – hence food – and then it only does so in 2 or 3 year intervals, not every year. Still, it is great for nesting and protection.

Nut trees of any sort are loved by our birds. You might wonder how acorns can be opened and eaten by small birds like the Carolina wren or white-breasted nuthatch. Think of acorns like money in the bank. No, most birds can’t crack them open when they fall. But a few months on the ground will soften the outer shell. And squirrels are messy eaters. They’ll open a nut, eat some, drop it and go on to the next – leaving plenty of nut meat for an industrious bird. Of course, nut trees take time to reach maturity, but plan now for your grandchildren’s enjoyment when adults.

Berries of any sort are great for birds. Wild grapes, for example, may be a pain if they grow up your favorite decorative tree, but in the woods they are fine. More than 50 species of birds eat the fruit, though that is mainly in the fall. They are beloved by birds we all love – cardinals, orioles and scarlet tanagers, along with the more common woodpeckers, warblers and thrushes.

Wild brambles grow freely along the edges of fields and gardens. Most gardeners think of them as pests and pull them out, but many birds like the fruit – even if it is not as sweet as our cultivated raspberries and blackberries. So let those brambles grow. Since they are thorny, cats are less likely to prowl in brambles, giving protection for nesting birds such as catbirds and vireos, which find them attractive.

Native shrubs are generally better for feeding birds than shrubs imported from Europe or the Far East. Why? Because our birds and our native shrubs evolved together, one adapting to the other. Birds that eat berries from native shrubs such as elderberries, viburnums and native willows and dogwoods produce better food for birds than non-native shrubs.

I don’t cut down all my perennial flowers in the fall. Not because I am lazy or behind on my work (though there is some of that). I leave things like purple coneflower and black-eyed Susans for the finches. Those flower heads are fully of little seeds. My sunflower seeds get eaten by birds in late summer or early fall, so there are none left for winter – except in 20 pound bags.

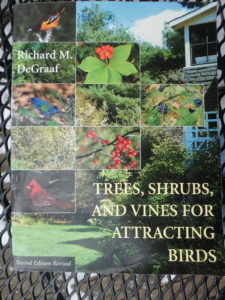

Winter is a good time for planning. If you like the idea of planting for birds, you should try to locate a copy of Richard DeGraf’s book, Trees, Shrubs and Vines for Attracting Birds. I think it’s out of print, but readily available. This book lists most common native species of trees, shrubs and vines and then specifically lists the birds that use them for food, nesting or cover. Thus if you want to attract cardinals or bluebirds, for example, study the book to see which plants are used by them.

As you reflect on what trees and shrubs to plant, remember that birds need more than food. They need nesting sites, protection from the wind and those sneaky neighborhood cats. There are plenty of native plants that will look good in your landscape, and support our feathered friends, too.

Henry is the author of 4 gardening books. He lives and gardens in Cornish Flat, NH.

Five Plants for Adding Indoor Color

This is the dark time of the year. The sun sets early, and is often obscured by clouds dripping rain and snow. For that reason, I string bright lights on trees outdoors, decorate a tree indoors, place candles in my windows – and lots more. I buy cut flowers, too, but I can’t afford to buy armloads of bright flowers every week. Fortunately the outdoors provides me with many nice things to brighten my living space.

One of my favorite shrubs at this time of year is winterberry (Ilex verticillata). You may have seen the bright red berries of wild winterberry growing alongside the road in wet places, often in standing water. It favors wet places, but can be grown in the average garden. In the wild it is an understory shrub, one that grows in partial shade. It produces the most berries, however, in full sun.

As a landscape plant, the winterberry is best in fall and winter when the red berries are prominent. The spring blossoms are small and white, and hardly noticeable. These shrubs are either male or female, and you need one male for every 6 to 10 females within about a 50-foot range. So when you buy winterberry, plan on having several. Unlike puppies, you can’t lift a tail and know what sex you are buying, but have to depend on the nursery to label them properly.

When you bring cut branches into the house and place them in a vase of water you will notice that they regularly drop berries. There is a solution: spray with a clear lacquer. Last year I sprayed branches that I used on my door wreath, and for the first time ever, most berries stayed on until I took down the wreath. Previously some of the berries fell off every time the door was closed.

Evergreen boughs are commonly used for indoor arrangements, sprays, kissing balls and garlands. If you plan to harvest evergreen branches on your own property for this, be sure to use branches that will hold onto their needles. Balsam fir and spruce, commonly used for Christmas trees, hold onto their needles well even when not in a vase of water. But most of us don’t want to cut off branches if we have balsam or spruce on the property.

What most of us have growing in our woods are white pine and Canadian hemlock. White pines hold their needles, hemlocks do not. The hemlocks have short needles arranged flat along the stems; they have 2 white stripes on the underneath side of each needle. White pine needles are long and pointy, but soft. They grow in bundles of 5 needles (one for each letter in the word ‘white’).

Of the ferns you might see in the woods now, only the Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides) is suitable for use in a vase. These have leathery green leaves with leaflets arranged in an alternating pattern. Some think the leaflets resemble a Christmas stocking, with a toe or heel at the end near its attachment point. I do not. I think they are called Christmas fern because they are still nice at Christmas and other ferns have largely disappeared by now.

Christmas ferns grow in shade or partial shade, and prefer somewhat moist locations. If you pick some, do not completely defoliate an individual plant. Take a few stems from one, and then a few from others. These plants are tough, but slow-growing.

What else is green and will do well indoors? Ground pine (Lycopodium obscurum) grows in deciduous forest in many of the same places as Christmas ferns. It is not a pine at all, but a club moss, a group of primitive plants that fed the dinosaurs when club mosses got to be 30 feet tall. These poor relatives only grow a few inches to a foot tall, but have handsome foliage in winter. They spread by rhizomes or roots. Each plant has leaves that come from the central spine of the plant, and lie parallel to the ground – like little Christmas trees. Please be judicious in picking these.

Back to the reds: red-twigged or redosier dogwood (Cornus sericea), a native of moist areas here in the Northeast, looks good in a vase. The color brightens up considerably in the winter, especially on this year’s growth. If the town road crew brush-hogged the roadside this summer, the new growth on red dogwood will be very bright.

Of course the plant nursery business has been working hard and breeding the reddest, brightest varieties and touting each of them as the very best. But all are good, and are very fast growing – especially in wet areas. I favor pruning out at least half the stems each year to get new stems with bright winter color, and have been known to cut a bush right to the ground.

So don’t feel bad if you can’t afford big vases of roses at this time of year. Get outside and pick some nice things that will brighten the house.

Read Henry’s blog at https://dailyuv.com/