Saving Seeds from Heirloom Vegetables

As a boy in the 1950’s I knew there were two kinds of tomatoes: deep red, plump and tasty ones my grandfather grew, and the kind that came four in a package wrapped in cellophane. The Cello-Wraps, as I think of them, had no flavor whatsoever. They were decorative. Sliced and added to our iceberg lettuce salads in winter, they added color. I suppose my mom thought they added some vitamins, too, but I doubt they contributed much.

Heirloom tomatoes are often irregular in size and shape but they are tasty and you can save seeds for the next year

My grandfather saved seeds from his tomatoes and started plants indoors in the early spring. He was not growing hybrid tomatoes like those sold in the supermarket. Hybrid tomatoes are carefully bred by crossing specific varieties of tomatoes so that they will have special characteristics such as surviving long trips in trucks, having a shelf life almost as long as a tennis ball, or resisting certain diseases. But those are not suitable for seed saving – most of their seeds will produce mongrels, not the variety you grew.

My grandfather grew what we now call heirloom tomatoes: time-tested varieties that breed true from seed, generation after generation. Tomatoes that had been grown for many decades, seed shared with family and friends. Tomatoes so tasty that they were often eaten right in the garden, warm from the sun.

Examples of well-known heirloom tomatoes include Brandywine (often touted as the best flavored tomato in existence), Cherokee Purple, Mortgage Lifter, Amish Paste and Black Krim. But there are hundreds of varieties of heirloom tomatoes. Each unique and loved by someone. Many have now disappeared – once a variety is lost, it cannot be brought back unless someone has saved the seeds so they can be grown again.

All heirloom vegetables are what are called “open pollinated” meaning that they will produce the same variety every year. Of course, in a packet of seeds some will produce better fruits than others. There is variety, but all Brandywines will take about the same length of time to reach maturity and taste about the same.

If you would like to start saving seeds, read the seed packet or catalog and make sure what you buy is labeled open-pollinated or heirloom, not hybrid. At the end of the season, save some seeds and store them in a cool, dry, dark place, perhaps in a sealed jar in a refrigerator. Then start them the following spring.

I called Sylvia Davatz, the now-retired founder of Solstice Seeds in Hartland, Vermont to talk about saving seeds. Solstice Seeds only grows and sells seeds from heirloom varieties including some varieties from Europe.

She gave me lots of good advice, starting with the names of two good books on seed saving: The Seed Garden by Lee Buttala and Sharyn Seigel, and The Manual of Seed Saving by Andrea Heistinger. She recommends getting both books if you are going to be serious about saving seeds as even among experts there are differences of opinion. These books will tell you all you need to know.

One of the reasons for having good books about seed saving is that they will advise you about such things as isolation distances to prevent mixing genetic material by pollinators or wind.

I asked Sylvia what vegetable species are the easiest to save. She said tomatoes, lettuce, beans and peas are all easy. They are self-pollinated and annuals. No insects are needed, and seeds are ready by the end of their season.

Vine crops like squash, pumpkins and cucumbers are insect pollinated and more difficult. If you’ve ever let a “pumpkin” grow in your compost pile from last year’s crop, you know that sometimes you get weird things due to cross pollination – a pumpkin crossed with a summer squash by a bee, for example, may not be something you want to eat.

Most difficult in our climate are the biennials, things like carrots, beets, parsnips and parsley. These plants have to be kept alive all winter so they can flower and set seeds in their second year. You can dig up carrots and store them in soil in a bucket in a cold basement and re-plant them in the spring. But carrots, Sylvia explained to me, bloom about the same time as Queen Anne’s lace, a biennial wild flower/weed that can be pollinated by them – which would not produce the carrots you want.

Sylvia pointed out that in the not-to-distant past, seed saving was the norm. Farmers and gardeners saved seeds from their best plants, knew how to do so, and how to store them. She explained that the seeds you save will usually be of better quality than seeds from a packet. They will have more vigor and a longer life span.

A good source for heirloom seeds is The Seed Savers Exchange. It has, since 1975, collected and stored seeds from gardeners and farmers. You can join their non-profit or just buy some seeds or books from them. According to their website, they now store some 20,000 varieties in their collection, although at any given time only a fraction of them are actually for sale.

So think about saving seeds this year – even if only a few from your favorite heirloom tomatoes. And go to www.solsticeseeds.org to see a wonderful 8 minute video of Sylvia Davatz explaining all the importance and benefits of seed saving.

Henry is the author of 4 gardening books and a lifetime organic gardener. He lives in Cornish Flat, NH. Reach him by e-mail at henry.homeyer@comcast.net

Planning a Garden in the Lawn

This is a good time to make plans. If you are willing to spend just 15 minutes a day, every day, from spring to fall you can create an edible showcase for beauty: the splendid look of ripe red tomatoes, multi-colored Swiss chard, or glossy green peppers. It’s not nearly as difficult as you think. And unlike maintaining a lawn, you get to eat the results of your labor. Here’s what you need to do:

Using string and stakes define the borders of the garden and pry out the sod after cutting it into 1-foot squares with an edging tool or a spade. Use the sod to start a compost pile.

Alternatively, you can build wood-sided beds using ordinary 6 or 8-inch wide planks. For more years of service, 2 inch thick lumber is even better. Gardener’s Supply (www.Gardeners.com) sells a variety of brackets for building raised beds, and I suppose others do, too.

If you make wood-sided beds you can place them right on the lawn without removing the sod, which saves a lot of labor. Just scalp the grass with the lawnmower and put a thick layer of newspapers over the lawn, then fill the box. Long carrots might hit the bottom the first year, but most other plants won’t be bothered.

The Spring Flower Shows Are Back!

The spring flower shows are always a contrast to the cold, icy days of winter. Bright flowers, garden paraphernalia and numerous workshops make these events fun – both for beginner and expert. Here is this year’s offerings, starting with the first ones in February and going on until May.

The first show of the season in a specialty show: orchids. The NH Orchid Society is holding its annual get-together February 10 to 12 at the Courtyard Marriott in Nashua, NH. This is THE show for orchid lovers. There will be vendors of orchids from Ecuador, Taiwan and the USA. Members of the Society will bring their orchids to compete and to strut their stuff. Admission is just $10 or $8 for seniors.

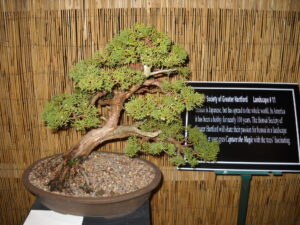

Next up is the Connecticut Flower and Garden Show February 23 to 26. This is a mammoth show with over three acres of displays. As always, it is being held at the Connecticut Convention Center in Hartford, CT. Tickets are $20 at the door, or $17 in advance. Kids 5 to 12 are $5.

One of the greatest things about this show are the educational seminars. Here are a few workshops that interest me: “Good Bug, Bad Bug, Benign Bug”. This is great for anyone who tends to squish any bug in the garden – even though most are not a problem. I assume there will be slides of insects we should recognize, but probably don’t. Then there is one on organic lawn care, another called, “Shady Characters”. I know garden writer Ellen Ecker Ogden of Vermont will do a nice slide presentation and talk about Kitchen Garden Design and how to make your veggies look artful. She always does.

One of my favorite shows is always the Vermont Flower Show. It will take place this year March 3 to 5 at the Champlain Valley Expo Center in Essex Junction, VT. The theme this year is “Out of Hibernation! Spring Comes to the 100-Acre Wood”, a tribute to Winnie the Pooh.

The main garden display is always a collaborative effort by members of the Vermont Nursery and Landscape Association. For three and a half days members of VNLA will work together to create a 15,000 square foot display using their own and donated materials. Other shows tend to have displays by professionals that are competing with each other, but not in Vermont – they work together.

If you plan to go to Chelsea, join the RHS to get better access times and pricing. Members get a discount of over $10 per day, but prices still range from $89 to $46 depending on the day of the week. British women tend to dress up for this show and wear big colorful hats. The first 2 days are for members only, so it should be a bit less crowded.

Growing Food for Taste and Flavor

We gardeners love our home grown vegetables. As John Denver sang long ago, “Only two things that money can’t buy and that’s true love and homegrown tomatoes.” And why do they taste so good? We can grow tomatoes that don’t have to conform to commercial requirements of size, shape, color and transportability. Our soils generally are rich in compost or manure and host a wide range of minerals and micro-organisms that enhance the flavors of our vegetables. And of course, we eat them fresh from the garden.

That book by Michael Abelman is called “Fields of Plenty: A Farmer’s Journey in Search of Real Food and the People Who Grow It”. Abelman, an experienced author and organic farmer in British Columbia, spent three months traveling around the States in a 15-year old VW van. He went with his 23-year old son back in 2004. They camped out, ate local food and met with organic farmers, some of whom were growing food for the best restaurants in America.

The book provides the names of many varieties of vegetables that are exceptional. Organic farmers Gene and Eileen Thiel of Joseph, Oregon specialize in potatoes, and particularly likes LaRatte, Yagana and Sante. Sante, he said, is like a Yukon Gold, but bigger. Yukon Gold also got high marks, as did Ranger Russets and Yellow Finn. He avoids losing his crop to blights, in part, by growing lots of different kinds of potatoes – as did the Incas, where potatoes came from. Of course there is no guarantee that a potato that does well in Oregon will do well for you.